*/

We’re having a constitutional moment... the Brexit process has exposed a dysfunctional relationship between law and politics in Westminster. Have we learned any lessons?

Brexit can plausibly be described as a ‘constitutional moment’. The decision to leave the EU will shape the UK constitution over the coming decades. Even if the full extent of the constitutional changes that will flow from Brexit are not yet known, future Prime Ministers will be defined (in part, at least) by their ability to oversee successful constitutional reform. The post-referendum period has revealed a great deal about the relationship between the UK’s political system and its constitutional framework. Those responsible for moving forward the constitution will need to learn the lessons from this tumultuous period.

One of the principal causes of the current crisis has been the way in which Theresa May’s government approached the task of governing without a majority. In the immediate aftermath of the referendum, members of the government stressed the need to deliver on the referendum result without delay. The overwhelming sentiment was that the government, led by the Prime Minister and her Cabinet, should be left to get on with the task of negotiating a deal: a majoritarian mindset disconnected from the reality of a divided Cabinet and Parliament. Instead, the government should have sought to build a majority for its proposed approach to delivering Brexit before it triggered Article 50 (or at the beginning of the 2017 Parliament).

Any future government that wishes to deliver constitutional change without a majority should look to the example of 2010 Coalition government. The coalition agreement struck between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats specified the constitutional changes that the two parties would agree to support. Theresa May’s government should have done the same and at the outset sought support for the substance of its approach for delivering Brexit.

The domestic process by which Brexit was to be delivered was not given sufficient attention early enough. Constitutional change gives rise to cross-cutting issues deserving of a special form of public and parliamentary scrutiny. In the absence of a rock-solid parliamentary majority, a special process needed to be constructed to deliver the constitutional transformation of the scale required by Brexit. The commitment to such a process at an early stage would have sent a positive message to other parties – and to the public – that the government was committed to finding a compromise that commanded wide support.

In the absence of a formal agreement with another party, the government could have sought to construct a bespoke process that might have facilitated cross-party support for delivering Brexit. In the early stages of the process, suggestions that Parliament should have more input in the negotiations were rejected on the basis that the government should not have its hands tied. Rather than treating these suggestions as an opportunity to bring MPs onside, they were treated as threats that could derail the process. Theresa May’s government only resorted to indicative votes and cross-party talks after the negotiations with the EU finished (and her deal or no deal strategy had failed) which did little to inspire the sense that the desire to engage was genuine.

The Article 50 process has demonstrated that Parliament is a powerful constitutional actor. Since the Withdrawal Agreement was published in November 2018, the majorities against the Withdrawal Agreement and against a no deal exit shaped the debate. However, the Article 50 process has also shown that Parliament’s influence on the substance of treaty negotiations and the legislative process is limited. Over the course of the 2017 Parliament, the House of Commons inched its way to more control through innovative uses of parliamentary procedure, such as through business of the House motions and the Humble Address. The problem is that MPs only realised the extent of their power when it was too late. This meant that compromises were put together and agreed in haste. Essentially, backbench MPs made the same mistake as the government by not prioritising their influence over the process at an earlier stage.

During the Brexit process, parliamentary scrutiny and debate has been characterised by some as anti-democratic. Yet one of the central tenets of liberal constitutionalism is that proposals to change the constitution should be subject to scrutiny and debate. Constitutional democracy is in a very difficult place if this scrutiny and debate is not valued and defended. The core of the case for a carefully constructed procedure for constitutional change is that it enhances the democratic legitimacy of the end-product. How can constitutional reformers build the case for properly constructed change, if deliberation itself is under-valued in UK political culture?

The House of Commons and the Civil Service are restricted in their ability to defend their constitutional role by the requirements of impartiality. So, advocates of constitutional democracy need to robustly defend the role that institutions play in empowering citizens through democratic deliberation. No one is suggesting that politicians or institutions should be free from criticism (on the contrary, criticism is critical to their health and development). However, Brexit has highlighted a need for the values that underpin the basic elements of the democratic process to be defended far more vigorously.

Prior to the referendum vote, the Vote Leave campaign demonstrated that a constitutional argument could be framed and communicated in a way that could cut through. Restoration of sovereignty (‘take back control’) was central to the Vote Leave campaign narrative. However, in the post-referendum period, the government struggled to find a way of communicating the message that leaving the EU with a deal would empower ordinary citizens.

Of course, the reality of constitutional change is more complex than the messaging during the referendum campaign conveyed. However, it is clear that the government’s constitutional ambition was limited by its ability to communicate the value of democratic institutions. Implementing Brexit through radical constitutional change (eg devolving power to English regions) would have required innovative ways of communicating this change to voters – and the government did not have this capacity.

The Brexit process has exposed a fairly dysfunctional relationship between law and politics in Westminster. Parliamentarians have often been called out for misunderstanding some of the legal fundamentals of the Brexit process. The level of understanding of international law and EU law has been particularly problematic (although this perhaps reflects the limited incentives that parliamentarians have so far had to engage with either of these areas of law). At the same time, it is important to recognise that lawyers are not best equipped to engage with politics. As a result, the process has often been characterised by a frustratingly circular discourse. To improve the quality of debate over constitutional change, we need to bridge the gap between law and politics.

It may be that the UK’s constitutional democracy is in such difficulty that it cannot be repaired through piecemeal change. However, a more radical constitutional overhaul (perhaps in the form of a written constitution) will require politicians that are willing to prioritise finding a new constitutional settlement to resolve the post-Brexit divisions. At present, there are very few frontline politicians that prominently advocate constitutional change. It is not a message that seems to garner support.

Professor Jeff King’s inaugural lecture, delivered at University College London in April 2018, persuasively argued that moving towards a written constitution in the UK would provide a means for citizens to take ownership over the UK’s constitutional democracy. In order to revitalise constitutional democracy in the UK post-Brexit, political leadership will need to harness this insight and communicate it to the public at large.

Dr Jack Simson Caird is a senior research fellow in Parliaments and the Rule of Law at the Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law. From 2015 to 2018, Jack was a researcher in the Commons Library.

Brexit can plausibly be described as a ‘constitutional moment’. The decision to leave the EU will shape the UK constitution over the coming decades. Even if the full extent of the constitutional changes that will flow from Brexit are not yet known, future Prime Ministers will be defined (in part, at least) by their ability to oversee successful constitutional reform. The post-referendum period has revealed a great deal about the relationship between the UK’s political system and its constitutional framework. Those responsible for moving forward the constitution will need to learn the lessons from this tumultuous period.

One of the principal causes of the current crisis has been the way in which Theresa May’s government approached the task of governing without a majority. In the immediate aftermath of the referendum, members of the government stressed the need to deliver on the referendum result without delay. The overwhelming sentiment was that the government, led by the Prime Minister and her Cabinet, should be left to get on with the task of negotiating a deal: a majoritarian mindset disconnected from the reality of a divided Cabinet and Parliament. Instead, the government should have sought to build a majority for its proposed approach to delivering Brexit before it triggered Article 50 (or at the beginning of the 2017 Parliament).

Any future government that wishes to deliver constitutional change without a majority should look to the example of 2010 Coalition government. The coalition agreement struck between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats specified the constitutional changes that the two parties would agree to support. Theresa May’s government should have done the same and at the outset sought support for the substance of its approach for delivering Brexit.

The domestic process by which Brexit was to be delivered was not given sufficient attention early enough. Constitutional change gives rise to cross-cutting issues deserving of a special form of public and parliamentary scrutiny. In the absence of a rock-solid parliamentary majority, a special process needed to be constructed to deliver the constitutional transformation of the scale required by Brexit. The commitment to such a process at an early stage would have sent a positive message to other parties – and to the public – that the government was committed to finding a compromise that commanded wide support.

In the absence of a formal agreement with another party, the government could have sought to construct a bespoke process that might have facilitated cross-party support for delivering Brexit. In the early stages of the process, suggestions that Parliament should have more input in the negotiations were rejected on the basis that the government should not have its hands tied. Rather than treating these suggestions as an opportunity to bring MPs onside, they were treated as threats that could derail the process. Theresa May’s government only resorted to indicative votes and cross-party talks after the negotiations with the EU finished (and her deal or no deal strategy had failed) which did little to inspire the sense that the desire to engage was genuine.

The Article 50 process has demonstrated that Parliament is a powerful constitutional actor. Since the Withdrawal Agreement was published in November 2018, the majorities against the Withdrawal Agreement and against a no deal exit shaped the debate. However, the Article 50 process has also shown that Parliament’s influence on the substance of treaty negotiations and the legislative process is limited. Over the course of the 2017 Parliament, the House of Commons inched its way to more control through innovative uses of parliamentary procedure, such as through business of the House motions and the Humble Address. The problem is that MPs only realised the extent of their power when it was too late. This meant that compromises were put together and agreed in haste. Essentially, backbench MPs made the same mistake as the government by not prioritising their influence over the process at an earlier stage.

During the Brexit process, parliamentary scrutiny and debate has been characterised by some as anti-democratic. Yet one of the central tenets of liberal constitutionalism is that proposals to change the constitution should be subject to scrutiny and debate. Constitutional democracy is in a very difficult place if this scrutiny and debate is not valued and defended. The core of the case for a carefully constructed procedure for constitutional change is that it enhances the democratic legitimacy of the end-product. How can constitutional reformers build the case for properly constructed change, if deliberation itself is under-valued in UK political culture?

The House of Commons and the Civil Service are restricted in their ability to defend their constitutional role by the requirements of impartiality. So, advocates of constitutional democracy need to robustly defend the role that institutions play in empowering citizens through democratic deliberation. No one is suggesting that politicians or institutions should be free from criticism (on the contrary, criticism is critical to their health and development). However, Brexit has highlighted a need for the values that underpin the basic elements of the democratic process to be defended far more vigorously.

Prior to the referendum vote, the Vote Leave campaign demonstrated that a constitutional argument could be framed and communicated in a way that could cut through. Restoration of sovereignty (‘take back control’) was central to the Vote Leave campaign narrative. However, in the post-referendum period, the government struggled to find a way of communicating the message that leaving the EU with a deal would empower ordinary citizens.

Of course, the reality of constitutional change is more complex than the messaging during the referendum campaign conveyed. However, it is clear that the government’s constitutional ambition was limited by its ability to communicate the value of democratic institutions. Implementing Brexit through radical constitutional change (eg devolving power to English regions) would have required innovative ways of communicating this change to voters – and the government did not have this capacity.

The Brexit process has exposed a fairly dysfunctional relationship between law and politics in Westminster. Parliamentarians have often been called out for misunderstanding some of the legal fundamentals of the Brexit process. The level of understanding of international law and EU law has been particularly problematic (although this perhaps reflects the limited incentives that parliamentarians have so far had to engage with either of these areas of law). At the same time, it is important to recognise that lawyers are not best equipped to engage with politics. As a result, the process has often been characterised by a frustratingly circular discourse. To improve the quality of debate over constitutional change, we need to bridge the gap between law and politics.

It may be that the UK’s constitutional democracy is in such difficulty that it cannot be repaired through piecemeal change. However, a more radical constitutional overhaul (perhaps in the form of a written constitution) will require politicians that are willing to prioritise finding a new constitutional settlement to resolve the post-Brexit divisions. At present, there are very few frontline politicians that prominently advocate constitutional change. It is not a message that seems to garner support.

Professor Jeff King’s inaugural lecture, delivered at University College London in April 2018, persuasively argued that moving towards a written constitution in the UK would provide a means for citizens to take ownership over the UK’s constitutional democracy. In order to revitalise constitutional democracy in the UK post-Brexit, political leadership will need to harness this insight and communicate it to the public at large.

Dr Jack Simson Caird is a senior research fellow in Parliaments and the Rule of Law at the Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law. From 2015 to 2018, Jack was a researcher in the Commons Library.

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

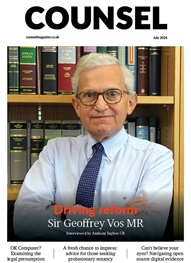

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts