*/

With a series of worked examples, Simon Levene guides beginners through the calculations in personal injury claims under the contentious new discount rate

On 27 February 2017 the Ministry of Justice announced a reduction of the discount rate from 2.50% to -0.75% with effect from 20 March 2017.

The implications of this change for the calculation of future losses in personal injury claims are enormous, because it greatly increased the value of such claims. This article guides beginners through the main sorts of calculations that they will come across in personal injury claims. The current edition of the Ogden Tables does not contain the figures discounted by -0.75%; these can be found here and in the 2017/18 edition of Facts & Figures, published on 31 August 2017.

To find a claimant’s life expectation, where there is no reason to think it might be shorter than the average, use Ogden Table 1 for men, and Table 2 for women. The figure that you see in the 0% column is the life expectation. (In fact, the Tables are based on slightly out-of-date life data, so the multipliers are a little low, but for the purpose of this article we will treat them as correct.) So:

There are 12 Ogden Tables for use in calculating future loss of earnings: Tables 3-14. These are for calculating loss of earnings to men’s and women’s retirement ages of 50, 55, 60, 65, 70 and 75. (If you need to calculate to different retirement ages – eg 66, 67, 68 or 69 – you will find these in Table A2 of ‘Facts & Figures – Tables for the Calculation of Damages’. The 2017/18 edition, which will be published shortly, will contain the -0.75% figures.)

To calculate future loss of earnings you will need to know the following about the claimant:

‘Disabled’, ‘employed’ and ‘not employed’, and the various levels of educational attainment, are defined in para 35 of the Introductory Notes to the Ogden Tables. The first seven factors give an indication of how much time the claimant would have spent in work if he had not been injured. If someone is currently in work, for example, he is likely on average to spend more of his future working years in work; if someone has a degree, he is likely to spend more time in work than someone with only two GCSEs; the able-bodied tend to spend more time in work than the disabled. These ‘reduction factors’ are brought together in Ogden Tables A-D. For example:

It is important to note that these are only average figures; it may be necessary to adjust them to take into account a claimant’s particular circumstances. Someone who has reached the age of 50 without ever doing a day’s work, for example, is likely to have a reduction factor of 0.00. Loss of three toes might be a disastrous injury for a footballer; it would probably not be so for a dermatologist.

The main difficulty in assessing a pension claim is establishing the annual loss, rather than the multipliers. The multipliers are found in Ogden Tables 15-26. It is worth bearing in mind that there is a relationship between a claimant’s pension and her earnings; when applying the adjustment factors of Tables A-D to the earnings figures, it may also be appropriate to take them into account when calculating future pension as well. After all, if a claimant had only been expected to spend, say, 82% of her future working life in work, that would presumably have affected her level of pension.

Table A6 in ‘Facts & Figures’ is a quick way of combining Ogden Tables 27 and 28 eg:

One is often faced with a claim for numerous aids and appliances, which will need replacement at different intervals eg:

For each such aid, you will need to find the claimant’s life expectation; you will find this in Ogden Table 1 or 2, in the 0% column. Let us say that the claimant will live for another 20 years. She will buy:

The time-consuming way of doing this is to do a separate calculation for every purchase of each item. Year 1 is the simple full cost, but there are nine further figures to look up in Table 27 – see Example 9 above (the car example) for how this is done.

The simpler way is to use Table A5 in ‘Facts & Figures’; this Table provides you with one combined figure for all the calculations. So, for example, [5.32 × £14] = £74, which is the total cost of buying one £14 walking stick now, and replacements in years 5, 9, 13 and 17.

This article has set out some of the most common calculations that will be needed when assessing future losses. There are more complicated calculations (eg where it is necessary to split the multipliers because there will be different losses at different times); and claims under the Fatal Accidents Act 1976 have their own pitfalls.

Contributor Simon Levene is a barrister at 12kbw

The implications of this change for the calculation of future losses in personal injury claims are enormous, because it greatly increased the value of such claims. This article guides beginners through the main sorts of calculations that they will come across in personal injury claims. The current edition of the Ogden Tables does not contain the figures discounted by -0.75%; these can be found here and in the 2017/18 edition of Facts & Figures, published on 31 August 2017.

To find a claimant’s life expectation, where there is no reason to think it might be shorter than the average, use Ogden Table 1 for men, and Table 2 for women. The figure that you see in the 0% column is the life expectation. (In fact, the Tables are based on slightly out-of-date life data, so the multipliers are a little low, but for the purpose of this article we will treat them as correct.) So:

There are 12 Ogden Tables for use in calculating future loss of earnings: Tables 3-14. These are for calculating loss of earnings to men’s and women’s retirement ages of 50, 55, 60, 65, 70 and 75. (If you need to calculate to different retirement ages – eg 66, 67, 68 or 69 – you will find these in Table A2 of ‘Facts & Figures – Tables for the Calculation of Damages’. The 2017/18 edition, which will be published shortly, will contain the -0.75% figures.)

To calculate future loss of earnings you will need to know the following about the claimant:

‘Disabled’, ‘employed’ and ‘not employed’, and the various levels of educational attainment, are defined in para 35 of the Introductory Notes to the Ogden Tables. The first seven factors give an indication of how much time the claimant would have spent in work if he had not been injured. If someone is currently in work, for example, he is likely on average to spend more of his future working years in work; if someone has a degree, he is likely to spend more time in work than someone with only two GCSEs; the able-bodied tend to spend more time in work than the disabled. These ‘reduction factors’ are brought together in Ogden Tables A-D. For example:

It is important to note that these are only average figures; it may be necessary to adjust them to take into account a claimant’s particular circumstances. Someone who has reached the age of 50 without ever doing a day’s work, for example, is likely to have a reduction factor of 0.00. Loss of three toes might be a disastrous injury for a footballer; it would probably not be so for a dermatologist.

The main difficulty in assessing a pension claim is establishing the annual loss, rather than the multipliers. The multipliers are found in Ogden Tables 15-26. It is worth bearing in mind that there is a relationship between a claimant’s pension and her earnings; when applying the adjustment factors of Tables A-D to the earnings figures, it may also be appropriate to take them into account when calculating future pension as well. After all, if a claimant had only been expected to spend, say, 82% of her future working life in work, that would presumably have affected her level of pension.

Table A6 in ‘Facts & Figures’ is a quick way of combining Ogden Tables 27 and 28 eg:

One is often faced with a claim for numerous aids and appliances, which will need replacement at different intervals eg:

For each such aid, you will need to find the claimant’s life expectation; you will find this in Ogden Table 1 or 2, in the 0% column. Let us say that the claimant will live for another 20 years. She will buy:

The time-consuming way of doing this is to do a separate calculation for every purchase of each item. Year 1 is the simple full cost, but there are nine further figures to look up in Table 27 – see Example 9 above (the car example) for how this is done.

The simpler way is to use Table A5 in ‘Facts & Figures’; this Table provides you with one combined figure for all the calculations. So, for example, [5.32 × £14] = £74, which is the total cost of buying one £14 walking stick now, and replacements in years 5, 9, 13 and 17.

This article has set out some of the most common calculations that will be needed when assessing future losses. There are more complicated calculations (eg where it is necessary to split the multipliers because there will be different losses at different times); and claims under the Fatal Accidents Act 1976 have their own pitfalls.

Contributor Simon Levene is a barrister at 12kbw

With a series of worked examples, Simon Levene guides beginners through the calculations in personal injury claims under the contentious new discount rate

On 27 February 2017 the Ministry of Justice announced a reduction of the discount rate from 2.50% to -0.75% with effect from 20 March 2017.

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

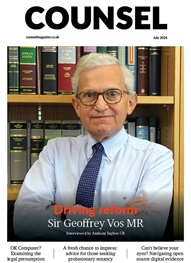

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts