*/

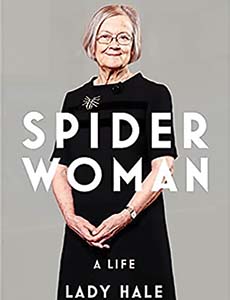

By Lady Hale

Lady Hale is a woman who has broken through the glass – and many other – ceilings. She has received numerous accolades over her career, including being the first judge to have a children’s book written about them (Equal to Everything: Judge Brenda and the Supreme Court, Afua Hirsch & Henny Beaumont, Legal Action Group: 2019).

Spider Woman: A Life operates at many different levels. It is almost several books in one. Most of all, though, it is full of human interest. She writes movingly about the death of her beloved husband. She describes the many times she felt imposter syndrome, starting at 10 years old at Richmond High School for Girls, a ‘speccy swot’ as she calls herself; at Girton College when she gains an exhibition; at the Law Commission where she was the youngest ever Law Commissioner; and then, most extraordinarily, when announcing the Supreme Court’s decision in the great Parliamentary promulgation case.

The book gives useful histories of the various institutions with which she has been associated and has much of interest to say on the creation of the Supreme Court. Lady Hale provides insights on many of the momentous cases in which she has been involved. She also describes the use of documents in the Supreme Court and how cases are decided. In some ways, this operates as a manual for advocates.

The four ‘in’ quotients necessary for judges she describes as intelligence, industry, independence and incorruptibility – all of which she has in abundance. She tells us that she enjoyed sitting in the Supreme Court more than the Court of Appeal, not least because the Supremes were ‘interested in the bigger picture: the social or economic context in which the problem arises’.

There are also fascinating sidelines, which will be of great interest to law students and legal observers, and even reference to storylines in The Archers.

Lady Hale recounts how she was attacked as ‘the most ideological, politically correct judge ever to have been appointed’ by one tabloid newspaper. This was, however, really a proxy for her feminism which is a major theme of the book. She is for affirmative action ‘to try and improve [judicial] selection criteria and processes’ but against quotas.

Feminism has been described by another judge as ‘Brenda’s agenda’. She covers many cases in which being a woman did make a difference to her contribution, although not always in the ways you might think. She is proud to relay the tribute paid to her by Dinah Rose QC in the valedictory ceremony in the Supreme Court as ‘a feminist, frank and fearless’ (and to use it as a chapter heading). Lady Hale recounts that she has never been afraid as a ‘soft feminist’ to ‘stand up for those beliefs’ but also records that ‘I have not always been popular for doing so’.

This book is not as earnest and pompous as some judicial memoirs. It does not have the humour of Lord Brown’s, nor the extraordinary indiscretion of Lord Hope’s. The latter was somewhat dismissive of Lady Hale on her appointment and said in his diary: ‘Brenda will be a source of some anxiety until we adjust to the very different contribution she will make.’ This she saw as ‘an unusually frank confession of the unease which even the most intelligent and otherwise fair-minded people can feel when confronted with a feminist agenda, as he called it’. Others would call it out as plain and simple misogyny. She does not respond in kind here, but rather with sadness and resignation.

She describes the book as ‘the story of how that little girl from a little school in a little village in North Yorkshire became the most senior judge in the UK. How she found that she could cope’.

Lady Hale has left a great legacy to the law and humanity. She will be forever immortalised by lawyers for delivering the unanimous decision of an 11-member court in the second Gina Miller case and by the public for the spider brooch which she wore when delivering it, which gives the book its title. She produces an elaborate explanation of why she wore that brooch; she says, for example, she was unaware of The Who’s song Boris the Spider ‘who comes to a sticky end’. I suggest respectfully that the public jury may not be sure that it was an accident!

Lady Hale is a woman who has broken through the glass – and many other – ceilings. She has received numerous accolades over her career, including being the first judge to have a children’s book written about them (Equal to Everything: Judge Brenda and the Supreme Court, Afua Hirsch & Henny Beaumont, Legal Action Group: 2019).

Spider Woman: A Life operates at many different levels. It is almost several books in one. Most of all, though, it is full of human interest. She writes movingly about the death of her beloved husband. She describes the many times she felt imposter syndrome, starting at 10 years old at Richmond High School for Girls, a ‘speccy swot’ as she calls herself; at Girton College when she gains an exhibition; at the Law Commission where she was the youngest ever Law Commissioner; and then, most extraordinarily, when announcing the Supreme Court’s decision in the great Parliamentary promulgation case.

The book gives useful histories of the various institutions with which she has been associated and has much of interest to say on the creation of the Supreme Court. Lady Hale provides insights on many of the momentous cases in which she has been involved. She also describes the use of documents in the Supreme Court and how cases are decided. In some ways, this operates as a manual for advocates.

The four ‘in’ quotients necessary for judges she describes as intelligence, industry, independence and incorruptibility – all of which she has in abundance. She tells us that she enjoyed sitting in the Supreme Court more than the Court of Appeal, not least because the Supremes were ‘interested in the bigger picture: the social or economic context in which the problem arises’.

There are also fascinating sidelines, which will be of great interest to law students and legal observers, and even reference to storylines in The Archers.

Lady Hale recounts how she was attacked as ‘the most ideological, politically correct judge ever to have been appointed’ by one tabloid newspaper. This was, however, really a proxy for her feminism which is a major theme of the book. She is for affirmative action ‘to try and improve [judicial] selection criteria and processes’ but against quotas.

Feminism has been described by another judge as ‘Brenda’s agenda’. She covers many cases in which being a woman did make a difference to her contribution, although not always in the ways you might think. She is proud to relay the tribute paid to her by Dinah Rose QC in the valedictory ceremony in the Supreme Court as ‘a feminist, frank and fearless’ (and to use it as a chapter heading). Lady Hale recounts that she has never been afraid as a ‘soft feminist’ to ‘stand up for those beliefs’ but also records that ‘I have not always been popular for doing so’.

This book is not as earnest and pompous as some judicial memoirs. It does not have the humour of Lord Brown’s, nor the extraordinary indiscretion of Lord Hope’s. The latter was somewhat dismissive of Lady Hale on her appointment and said in his diary: ‘Brenda will be a source of some anxiety until we adjust to the very different contribution she will make.’ This she saw as ‘an unusually frank confession of the unease which even the most intelligent and otherwise fair-minded people can feel when confronted with a feminist agenda, as he called it’. Others would call it out as plain and simple misogyny. She does not respond in kind here, but rather with sadness and resignation.

She describes the book as ‘the story of how that little girl from a little school in a little village in North Yorkshire became the most senior judge in the UK. How she found that she could cope’.

Lady Hale has left a great legacy to the law and humanity. She will be forever immortalised by lawyers for delivering the unanimous decision of an 11-member court in the second Gina Miller case and by the public for the spider brooch which she wore when delivering it, which gives the book its title. She produces an elaborate explanation of why she wore that brooch; she says, for example, she was unaware of The Who’s song Boris the Spider ‘who comes to a sticky end’. I suggest respectfully that the public jury may not be sure that it was an accident!

By Lady Hale

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts