*/

Raising discrimination issues can be tricky at the best of times; even more so when it’s you who’s dropped from a case. A first-hand account of the difficulties in challenging the status quo and growing will for change

British-Afghan barrister ‘overwhelmed’ by support after ‘white male’ request

Law Gazette, 8 November 2018

England’s only female Afghan barrister sacked because client wanted a white man

Metro Newspaper, 9 November 2018

The Rehana Popal discrimination case shows the need for legal diversity

CEDR Insights, 9 November 2018

Ditched Asian lawyer Rehana Popal had been stripped of 6 cases

The Times, 10 November 2018

I was very excited when first approached to write this article. As I put pen to paper, though, the difficulty in writing such a piece began to dawn on me. I did not want to be labelled as a ‘moaning myrtle’ or accused of staging a publicity stunt – both examples of the kind of comments that I received. Raising discrimination issues are tricky at the ‘best’ of times; even more so when it happens to you.

The aim of this piece is not to criticise any individuals or institutions. It is simply to demonstrate how difficult it can be to raise these kinds of matters – particularly when they challenge the status quo. More importantly, I want this article to raise awareness and, most crucially, highlight what more can be done.

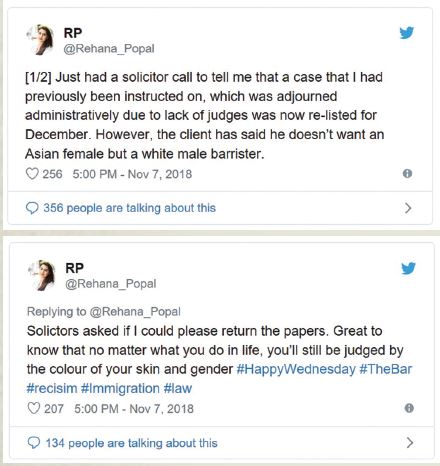

On 7 November 2018 I tweeted a conversation that I had with a solicitor:

The magnitude of what was said to me did not register at first. After all, this wasn’t the first time I’d been dropped from a case because of my gender or race and I thought it probably wouldn’t be the last.

At that stage I only had a few hundred followers and my tweets did not particularly attract attention. I thought that this tweet would also go unnoticed. I certainly did not expect it to go viral and prompt such a strong reaction.

What surprised me most was the polarised opinion from the legal world. With the exception of trolls and meanies (whom I am pleased to say were the minority), the reaction was overwhelming supportive. However, that support fell within two camps. The first expressed utter shock that this had happened. The second, who had experienced something similar, were unsurprised – and pleased that I had raised it.

I don’t need to tell readers of Counsel that forging a legal career is challenging. That challenge is made even greater by obstacles arising from discrimination.

After my tweet, it quickly became evident that my experience was not unique. Practitioners from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds and women barristers seemed especially unsurprised. I suspect that many of them had been a victim of such behaviour in the past or knew someone who had. Many will have got to the Bar against the odds. Rocking the boat or challenging the status quo is something that they can find particularly difficult; there’s a genuine fear that ‘making a fuss’ will have a negative impact on their career. The more ‘traditional’ members of the Bar don’t tend to face these kind of mental, emotional and professional obstacles.

One lesson to take away is this: there should be better ways for victims to raise such issues, without feeling that they are putting their careers on the line or opening themselves up to scrutiny. This is especially important for those at the junior end of the profession.

One suggestion repeatedly made on social media was that I should report the solicitor in question to the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA). Fellow tweeters argued that the solicitor had breached the SRA code of conduct by acting upon the client’s discriminatory instructions.

"Support fell within two camps. The first expressed utter shock that this had happened. The second, who had experienced something similar, were unsurprised – and pleased that I had raised it."

The legal world is small. It’s four degrees of separation rather than six. When you’re trying to build your practice, the last thing you want to be known as is a troublemaker. A barrister is only as good as their next brief. As a self-employed counsel, building a good relationship with solicitors is crucial. In situations such as this, the reality of the power dynamic between you and the instructing solicitor, especially when you are a junior barrister, truly hits home.

So how to handle awkward situations with instructing solicitors? I do not think there is a simple solution. The only way junior counsel may feel confident in raising such an issue is by having strong, formal and institutional support networks at the Bar eg chambers, the Inns of Court, Bar Council and Circuits. Informal networks, such as the Temple Women’s Forum and the Society of Asian Lawyers also play a vital role in providing pastoral support and professional advice.

Although, on the face of it, my solicitor had acted in breach of their code of conduct, I don’t blame them. It was not the solicitor who wanted to dis-instruct me. They felt that they could tell me the truth, and this is because of the good relationship that we have.

Reporting them would not address the root cause of the problem, nor make a material difference to the client’s instructions. If I made my solicitor the ‘scapegoat’, they may no longer have been so honest with me; and any future reasons for dis-instructing may just have been packaged in a different way.

Like counsel, solicitors are only as good as their next client. They are placed in a difficult position when a client makes such a request, particularly when they are well connected and/or influential within the circles that the solicitors operate. In my opinion, it would have been foolish and simplistic to blame the solicitor.

What was made clear to me by my instructing solicitor was that the client thought a judge would be more persuaded by a white male, ie a person who the client considered to look like the judge. This is the real problem. Reporting my solicitor was not going to change this client’s perception of the justice system, however incorrect or prejudiced.

We cannot escape the fact that the judiciary is overwhelmingly male and Caucasian. Great efforts have been made in recent years to diversify the judiciary and encourage applications to join the bench by those under represented. The fruit of these efforts, at the most senior end, will not be seen for years to come.

It is important that the Bar continues its efforts to diversify; the judiciary needs a diverse pool of talent from which to appoint. Recruiting and retaining diverse talent at the Bar is therefore crucial.

Whilst the Bar has made significant strides in enabling those from under-represented backgrounds to join, more can and should be done. We place a heavy emphasis on academic achievements. A tick box approach is the norm. Hardly any consideration is given to the way in which candidates for pupillage have obtained their grades – particularly at ‘A’ level stage. We know that an A* gained at a state school in a deprived area is harder to obtain than an A* gained at a well-resourced, fee-paying school. I am heartened by the fact that the legal profession is beginning to recognise this. Several magic circle firms and 20 Essex St Chambers are working with recruitment company Rare, which has developed a contextual recruitment system. This system allows recruiters to see candidates’ achievements in the context of which they were gained – taking into consideration postcode, school quality, eligibility for free school meal, refugee status and time spent in care

Initiatives like this are positive, practical and easy to implement. All that’s needed is the will – and one thing my experience has shown me is that there is more of a will out there than I’d thought. This is something the Bar must embrace and build upon.

The Law Society President, Christina Blacklaws told the Law Gazette at the time (8/11/2018): ‘What we can be clear about is that solicitors must not discriminate unlawfully against anyone on the grounds of any protected characteristic. A solicitor should refuse their client’s instruction if it involves the solicitor in a breach of the law or the code of conduct. Where a solicitor realises they have breached the code they may have a duty to report themselves to the regulator.’

Chair of the Bar 2018, Andrew Walker QC said at the time (9/11/18): ‘Discrimination against a barrister on the basis of a protected characteristic is completely unacceptable. The Bar Council is fully committed to supporting members of the Bar in tackling discrimination in all circumstances. As part of this, we take the issue of fair access to work extremely seriously, and provide clear guidance for barristers and their clerks on dealing with discriminatory instructions. Instructions which seek to discriminate against barristers, whether on the grounds of gender, race, age or any other protected characteristic, must be refused.’ See The Bar Council Ethics & Practice: Discriminatory Instructions page. Equality and diversity hotline: 020 7611 1426.

Rehana Popal is an immigration and public law specialist with particular expertise in asylum, immigration, and discrimination claims. Rehana is the first Afghan national to be called to the Bar by Inner Temple and is the only female Afghan barrister currently practising in England and Wales.

© iStockphoto/francescoch

British-Afghan barrister ‘overwhelmed’ by support after ‘white male’ request

Law Gazette, 8 November 2018

England’s only female Afghan barrister sacked because client wanted a white man

Metro Newspaper, 9 November 2018

The Rehana Popal discrimination case shows the need for legal diversity

CEDR Insights, 9 November 2018

Ditched Asian lawyer Rehana Popal had been stripped of 6 cases

The Times, 10 November 2018

I was very excited when first approached to write this article. As I put pen to paper, though, the difficulty in writing such a piece began to dawn on me. I did not want to be labelled as a ‘moaning myrtle’ or accused of staging a publicity stunt – both examples of the kind of comments that I received. Raising discrimination issues are tricky at the ‘best’ of times; even more so when it happens to you.

The aim of this piece is not to criticise any individuals or institutions. It is simply to demonstrate how difficult it can be to raise these kinds of matters – particularly when they challenge the status quo. More importantly, I want this article to raise awareness and, most crucially, highlight what more can be done.

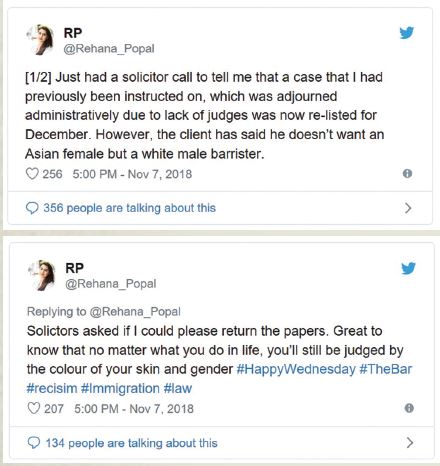

On 7 November 2018 I tweeted a conversation that I had with a solicitor:

The magnitude of what was said to me did not register at first. After all, this wasn’t the first time I’d been dropped from a case because of my gender or race and I thought it probably wouldn’t be the last.

At that stage I only had a few hundred followers and my tweets did not particularly attract attention. I thought that this tweet would also go unnoticed. I certainly did not expect it to go viral and prompt such a strong reaction.

What surprised me most was the polarised opinion from the legal world. With the exception of trolls and meanies (whom I am pleased to say were the minority), the reaction was overwhelming supportive. However, that support fell within two camps. The first expressed utter shock that this had happened. The second, who had experienced something similar, were unsurprised – and pleased that I had raised it.

I don’t need to tell readers of Counsel that forging a legal career is challenging. That challenge is made even greater by obstacles arising from discrimination.

After my tweet, it quickly became evident that my experience was not unique. Practitioners from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) backgrounds and women barristers seemed especially unsurprised. I suspect that many of them had been a victim of such behaviour in the past or knew someone who had. Many will have got to the Bar against the odds. Rocking the boat or challenging the status quo is something that they can find particularly difficult; there’s a genuine fear that ‘making a fuss’ will have a negative impact on their career. The more ‘traditional’ members of the Bar don’t tend to face these kind of mental, emotional and professional obstacles.

One lesson to take away is this: there should be better ways for victims to raise such issues, without feeling that they are putting their careers on the line or opening themselves up to scrutiny. This is especially important for those at the junior end of the profession.

One suggestion repeatedly made on social media was that I should report the solicitor in question to the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA). Fellow tweeters argued that the solicitor had breached the SRA code of conduct by acting upon the client’s discriminatory instructions.

"Support fell within two camps. The first expressed utter shock that this had happened. The second, who had experienced something similar, were unsurprised – and pleased that I had raised it."

The legal world is small. It’s four degrees of separation rather than six. When you’re trying to build your practice, the last thing you want to be known as is a troublemaker. A barrister is only as good as their next brief. As a self-employed counsel, building a good relationship with solicitors is crucial. In situations such as this, the reality of the power dynamic between you and the instructing solicitor, especially when you are a junior barrister, truly hits home.

So how to handle awkward situations with instructing solicitors? I do not think there is a simple solution. The only way junior counsel may feel confident in raising such an issue is by having strong, formal and institutional support networks at the Bar eg chambers, the Inns of Court, Bar Council and Circuits. Informal networks, such as the Temple Women’s Forum and the Society of Asian Lawyers also play a vital role in providing pastoral support and professional advice.

Although, on the face of it, my solicitor had acted in breach of their code of conduct, I don’t blame them. It was not the solicitor who wanted to dis-instruct me. They felt that they could tell me the truth, and this is because of the good relationship that we have.

Reporting them would not address the root cause of the problem, nor make a material difference to the client’s instructions. If I made my solicitor the ‘scapegoat’, they may no longer have been so honest with me; and any future reasons for dis-instructing may just have been packaged in a different way.

Like counsel, solicitors are only as good as their next client. They are placed in a difficult position when a client makes such a request, particularly when they are well connected and/or influential within the circles that the solicitors operate. In my opinion, it would have been foolish and simplistic to blame the solicitor.

What was made clear to me by my instructing solicitor was that the client thought a judge would be more persuaded by a white male, ie a person who the client considered to look like the judge. This is the real problem. Reporting my solicitor was not going to change this client’s perception of the justice system, however incorrect or prejudiced.

We cannot escape the fact that the judiciary is overwhelmingly male and Caucasian. Great efforts have been made in recent years to diversify the judiciary and encourage applications to join the bench by those under represented. The fruit of these efforts, at the most senior end, will not be seen for years to come.

It is important that the Bar continues its efforts to diversify; the judiciary needs a diverse pool of talent from which to appoint. Recruiting and retaining diverse talent at the Bar is therefore crucial.

Whilst the Bar has made significant strides in enabling those from under-represented backgrounds to join, more can and should be done. We place a heavy emphasis on academic achievements. A tick box approach is the norm. Hardly any consideration is given to the way in which candidates for pupillage have obtained their grades – particularly at ‘A’ level stage. We know that an A* gained at a state school in a deprived area is harder to obtain than an A* gained at a well-resourced, fee-paying school. I am heartened by the fact that the legal profession is beginning to recognise this. Several magic circle firms and 20 Essex St Chambers are working with recruitment company Rare, which has developed a contextual recruitment system. This system allows recruiters to see candidates’ achievements in the context of which they were gained – taking into consideration postcode, school quality, eligibility for free school meal, refugee status and time spent in care

Initiatives like this are positive, practical and easy to implement. All that’s needed is the will – and one thing my experience has shown me is that there is more of a will out there than I’d thought. This is something the Bar must embrace and build upon.

The Law Society President, Christina Blacklaws told the Law Gazette at the time (8/11/2018): ‘What we can be clear about is that solicitors must not discriminate unlawfully against anyone on the grounds of any protected characteristic. A solicitor should refuse their client’s instruction if it involves the solicitor in a breach of the law or the code of conduct. Where a solicitor realises they have breached the code they may have a duty to report themselves to the regulator.’

Chair of the Bar 2018, Andrew Walker QC said at the time (9/11/18): ‘Discrimination against a barrister on the basis of a protected characteristic is completely unacceptable. The Bar Council is fully committed to supporting members of the Bar in tackling discrimination in all circumstances. As part of this, we take the issue of fair access to work extremely seriously, and provide clear guidance for barristers and their clerks on dealing with discriminatory instructions. Instructions which seek to discriminate against barristers, whether on the grounds of gender, race, age or any other protected characteristic, must be refused.’ See The Bar Council Ethics & Practice: Discriminatory Instructions page. Equality and diversity hotline: 020 7611 1426.

Rehana Popal is an immigration and public law specialist with particular expertise in asylum, immigration, and discrimination claims. Rehana is the first Afghan national to be called to the Bar by Inner Temple and is the only female Afghan barrister currently practising in England and Wales.

© iStockphoto/francescoch

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts