*/

We defend fearlessly our clients’ best interests and fight for the underdog every day in court, but neglect to apply that same attitude to ourselves. What is needed to improve the lives of those who seek to stand up for justice and assure the future of the profession?

By Siân Beaven

Like many reading this piece, I joined the criminal Bar fuelled by lofty principles of ‘justice,’ ‘fair play’ and giving a voice to those who were unable to speak for themselves. No one of my generation of lawyers went into a legal aid practice with their eyes shut. Every pupillage interview and networking event seeks to test your mettle on how much you want this area of law, how tough it will be – the clients, the harrowing stories, the crippling lack of payment and the gruelling hours. After a childhood of watching Rumpole and Kavanagh, my cohort entered the profession knowing full-well that the days of economic prosperity were over. That said, much like our colleagues in medicine and social care, for whom we all stood on our doorsteps earlier this year and clapped our appreciation, there remained a dedicated cluster of young lawyers every year, prepared to overlook all the negatives, and to give themselves to the vocation that is criminal justice.

Then coronavirus came knocking.

As barristers we are used to rolling with the punches. You can never plan for everything and certainly, nobody planned for this. Overnight, practices were decimated and what was left was changed beyond recognition and confined to a virtual prism. We weathered that as best we could.

As lockdown eased, and the world began to reopen including courts, the environment once again shifted, and the problems faced by the profession changed. The virus had seeped its way into the cracks in the foundation of our under-funded, under-recognised justice system and had blown them into gaping holes. Those who worked in the system, much like our colleagues in health and care, had held it together by what felt like an endless stream of goodwill, often at great personal expense.

The new proposals to tackle what has now been recognised, even within the mainstream media as a crisis, have been widely criticised by the community of lawyers who acknowledge that we, as practitioners are at the sharp end of a problem that was not of our creation. Neither the systemic underfunding, nor the onset of an international pandemic was of our design, yet somehow the expectation was that we would enable the solution at no additional cost to the state but great personal burden.

It struck me, upon reading these critiques from our representative bodies and from vocal advocates on social media that it is enshrined in our code of ethics that we defend ‘fearlessly’ our client’s best interests. We fight for the underdog with all we’ve got every day in court, and we recognise the importance of having an independent profession that is able and willing to do that. So, while we tackle every problem in a case head on for the good of those we represent, it appears we are neglecting to apply that same attitude to the bigger battle, the one for the future of our profession. Perhaps, if I may be so dramatic, the future of justice as we know it in this country.

This summer alone the profession has faced some serious threats. There is hardship on an individual and chambers basis which threatens the financial survival of a wealth of talent and, I fear, the loss of many hardworking, decent and principled people to any profession where their skills and tenacity are valued. But, just as crucially as the fear of an exodus, there is the question of those who stick it out.

‘Extended hours’ has been the principal and most controversial proposal. The profession recognises the real and cogent risk that parents and caregivers, disproportionately women, will be forced out of the profession if this was to become the norm. A recent Women in Criminal Law survey demonstrates the overwhelming opposition to this policy citing concerns over lack of work-life balance as a principal reason. Promises of this only ‘being a temporary measure’ have been met with distrust given that it is likely to prove a very effective means of ensuring more hours are derived from the same fees (in effect, a pay cut). Diversity that has been hard fought for will be reversed. It is one thing to put ourselves through the rollercoaster of life at the Bar, quite another to inflict the uncertainty and stress on our families and children and therefore people will make difficult choices, probably sooner than we think. For those left – however talented and dedicated, however good at one’s job – we will be running on even less sleep, less leisure time and increased stress and unpredictability within caseloads. Whose best interest will we be serving then?

The inhumanity within our profession is growing everywhere we look. While extended hours is only officially piloting in a handful of courts, it is alive and well and coming through the back door of many magistrates’ courts in particular. These are the usual habitats of our youngest and most vulnerable colleagues, often desperate to impress chambers and solicitors alike, without savings or other financial support, working for below the minimum wage. Harrowing stories of anonymous tweets from pupils tell of a generation at the very beginning of their careers at ‘breaking point’ at court until well into the night and working later still to prepare for the next day.

During the heatwave, so as to comply with COVID-19 restrictions, lawyers were being denied water in courtrooms. Some were then being denied a lunch break to obtain any themselves because, the parties ‘needed to keep negotiating over lunch’ by judicial instruction. It is hard to imagine another working environment where this would be considered acceptable treatment.

This was perhaps shown off at its best during the Bar Professional Training Course centralised exams when students were expected to urinate into bottles, and refrain from averting their eyes from their screens for fear of having their exams terminated. This was after reports of scores of students having prolific tech problems preventing them from even completing the test. These are the future of the profession, people that haven’t yet got so much as a foot in the door and already they have experienced the appalling (but perhaps not in reality all that shocking) treatment that many in the profession have come to expect.

With courts now desperate to utilise what little space is open for trials, complex cases are being called on spontaneously, at a moment’s notice, well before they are actually ready to be heard. We can hardly call this justice for the clients we serve and, however much we as professionals are used to enduring, we cannot survive indefinitely in this state of economic and professional uncertainty. Court users are now having to wait an exorbitant amount of time to hear their cases, impacting upon both their psychological wellbeing and their ability to recall the events in question. Practitioners are caught in a seemingly endless cycle whereby cases are not concluding and therefore their caseloads are swelling, requiring more mental gymnastics than ever before.

So, what is needed to improve the lives of those who seek to stand up for justice? The simple answer as we all know is investment, and there are plenty of sources out there from greater minds than mine about how and where that money should be put to use – if it were ever to be forthcoming.

But I think, in the absence of that, the big ones for the profession are solidarity and awareness. For those that have influence and gravitas, use that soft power. As trials come back into lists, with priority being given to custody cases, more serious cases, those with complexity or witness vulnerability, spare a thought that this will benefit more senior practitioners faster than it will those who are junior. Remember to ‘temperature check’ your juniors and see how things really are for them. Issues such as de-facto extended hours and finding yourself at the wrong end of judicial frustrations in these trying times are disproportionately likely to impact upon the younger end. This was demonstrated beautifully by the recent kind pledge by Keating Chambers to finance a criminal pupillage in recognition of the acute difficulties faced by many criminal sets and the value of the criminal Bar. Solidarity needs to extend across the legal professions and from the judiciary to the Bar in recognition that, in these immensely challenging times both personally and professionally, everyone is doing their best.

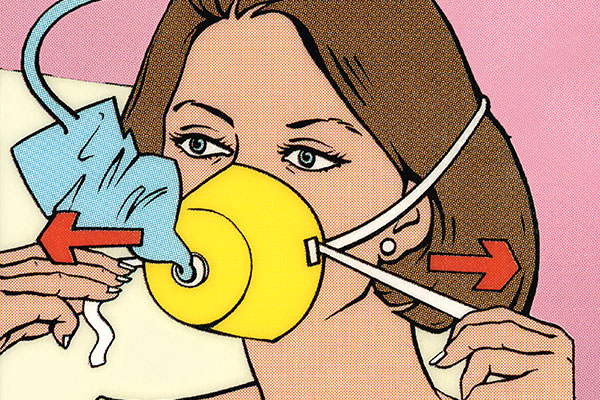

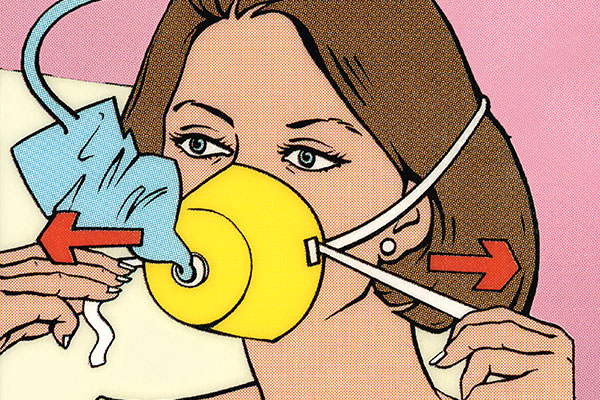

Finally, in order to improve wellbeing during what is undoubtedly some of the most trying times for our profession, we need leadership. Be that active heads of chambers looking out for their colleagues, all the way up to our elected representatives on Circuit and associations, we need these people to be brave, to be clear and to stand up for the vocation that we all hold in such high esteem that we have dedicated our lives to it. This is the long game. But if we’re going to play it that way, we have to start standing up for the little guys that are holding the system together each day, so that we can keep standing up for those people we represent. Because, just like when a plane goes down, you are advised to ‘fit your own oxygen mask first’, we cannot provide the service our clients deserve if we don’t first preserve ourselves.

Like many reading this piece, I joined the criminal Bar fuelled by lofty principles of ‘justice,’ ‘fair play’ and giving a voice to those who were unable to speak for themselves. No one of my generation of lawyers went into a legal aid practice with their eyes shut. Every pupillage interview and networking event seeks to test your mettle on how much you want this area of law, how tough it will be – the clients, the harrowing stories, the crippling lack of payment and the gruelling hours. After a childhood of watching Rumpole and Kavanagh, my cohort entered the profession knowing full-well that the days of economic prosperity were over. That said, much like our colleagues in medicine and social care, for whom we all stood on our doorsteps earlier this year and clapped our appreciation, there remained a dedicated cluster of young lawyers every year, prepared to overlook all the negatives, and to give themselves to the vocation that is criminal justice.

Then coronavirus came knocking.

As barristers we are used to rolling with the punches. You can never plan for everything and certainly, nobody planned for this. Overnight, practices were decimated and what was left was changed beyond recognition and confined to a virtual prism. We weathered that as best we could.

As lockdown eased, and the world began to reopen including courts, the environment once again shifted, and the problems faced by the profession changed. The virus had seeped its way into the cracks in the foundation of our under-funded, under-recognised justice system and had blown them into gaping holes. Those who worked in the system, much like our colleagues in health and care, had held it together by what felt like an endless stream of goodwill, often at great personal expense.

The new proposals to tackle what has now been recognised, even within the mainstream media as a crisis, have been widely criticised by the community of lawyers who acknowledge that we, as practitioners are at the sharp end of a problem that was not of our creation. Neither the systemic underfunding, nor the onset of an international pandemic was of our design, yet somehow the expectation was that we would enable the solution at no additional cost to the state but great personal burden.

It struck me, upon reading these critiques from our representative bodies and from vocal advocates on social media that it is enshrined in our code of ethics that we defend ‘fearlessly’ our client’s best interests. We fight for the underdog with all we’ve got every day in court, and we recognise the importance of having an independent profession that is able and willing to do that. So, while we tackle every problem in a case head on for the good of those we represent, it appears we are neglecting to apply that same attitude to the bigger battle, the one for the future of our profession. Perhaps, if I may be so dramatic, the future of justice as we know it in this country.

This summer alone the profession has faced some serious threats. There is hardship on an individual and chambers basis which threatens the financial survival of a wealth of talent and, I fear, the loss of many hardworking, decent and principled people to any profession where their skills and tenacity are valued. But, just as crucially as the fear of an exodus, there is the question of those who stick it out.

‘Extended hours’ has been the principal and most controversial proposal. The profession recognises the real and cogent risk that parents and caregivers, disproportionately women, will be forced out of the profession if this was to become the norm. A recent Women in Criminal Law survey demonstrates the overwhelming opposition to this policy citing concerns over lack of work-life balance as a principal reason. Promises of this only ‘being a temporary measure’ have been met with distrust given that it is likely to prove a very effective means of ensuring more hours are derived from the same fees (in effect, a pay cut). Diversity that has been hard fought for will be reversed. It is one thing to put ourselves through the rollercoaster of life at the Bar, quite another to inflict the uncertainty and stress on our families and children and therefore people will make difficult choices, probably sooner than we think. For those left – however talented and dedicated, however good at one’s job – we will be running on even less sleep, less leisure time and increased stress and unpredictability within caseloads. Whose best interest will we be serving then?

The inhumanity within our profession is growing everywhere we look. While extended hours is only officially piloting in a handful of courts, it is alive and well and coming through the back door of many magistrates’ courts in particular. These are the usual habitats of our youngest and most vulnerable colleagues, often desperate to impress chambers and solicitors alike, without savings or other financial support, working for below the minimum wage. Harrowing stories of anonymous tweets from pupils tell of a generation at the very beginning of their careers at ‘breaking point’ at court until well into the night and working later still to prepare for the next day.

During the heatwave, so as to comply with COVID-19 restrictions, lawyers were being denied water in courtrooms. Some were then being denied a lunch break to obtain any themselves because, the parties ‘needed to keep negotiating over lunch’ by judicial instruction. It is hard to imagine another working environment where this would be considered acceptable treatment.

This was perhaps shown off at its best during the Bar Professional Training Course centralised exams when students were expected to urinate into bottles, and refrain from averting their eyes from their screens for fear of having their exams terminated. This was after reports of scores of students having prolific tech problems preventing them from even completing the test. These are the future of the profession, people that haven’t yet got so much as a foot in the door and already they have experienced the appalling (but perhaps not in reality all that shocking) treatment that many in the profession have come to expect.

With courts now desperate to utilise what little space is open for trials, complex cases are being called on spontaneously, at a moment’s notice, well before they are actually ready to be heard. We can hardly call this justice for the clients we serve and, however much we as professionals are used to enduring, we cannot survive indefinitely in this state of economic and professional uncertainty. Court users are now having to wait an exorbitant amount of time to hear their cases, impacting upon both their psychological wellbeing and their ability to recall the events in question. Practitioners are caught in a seemingly endless cycle whereby cases are not concluding and therefore their caseloads are swelling, requiring more mental gymnastics than ever before.

So, what is needed to improve the lives of those who seek to stand up for justice? The simple answer as we all know is investment, and there are plenty of sources out there from greater minds than mine about how and where that money should be put to use – if it were ever to be forthcoming.

But I think, in the absence of that, the big ones for the profession are solidarity and awareness. For those that have influence and gravitas, use that soft power. As trials come back into lists, with priority being given to custody cases, more serious cases, those with complexity or witness vulnerability, spare a thought that this will benefit more senior practitioners faster than it will those who are junior. Remember to ‘temperature check’ your juniors and see how things really are for them. Issues such as de-facto extended hours and finding yourself at the wrong end of judicial frustrations in these trying times are disproportionately likely to impact upon the younger end. This was demonstrated beautifully by the recent kind pledge by Keating Chambers to finance a criminal pupillage in recognition of the acute difficulties faced by many criminal sets and the value of the criminal Bar. Solidarity needs to extend across the legal professions and from the judiciary to the Bar in recognition that, in these immensely challenging times both personally and professionally, everyone is doing their best.

Finally, in order to improve wellbeing during what is undoubtedly some of the most trying times for our profession, we need leadership. Be that active heads of chambers looking out for their colleagues, all the way up to our elected representatives on Circuit and associations, we need these people to be brave, to be clear and to stand up for the vocation that we all hold in such high esteem that we have dedicated our lives to it. This is the long game. But if we’re going to play it that way, we have to start standing up for the little guys that are holding the system together each day, so that we can keep standing up for those people we represent. Because, just like when a plane goes down, you are advised to ‘fit your own oxygen mask first’, we cannot provide the service our clients deserve if we don’t first preserve ourselves.

We defend fearlessly our clients’ best interests and fight for the underdog every day in court, but neglect to apply that same attitude to ourselves. What is needed to improve the lives of those who seek to stand up for justice and assure the future of the profession?

By Siân Beaven

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts