*/

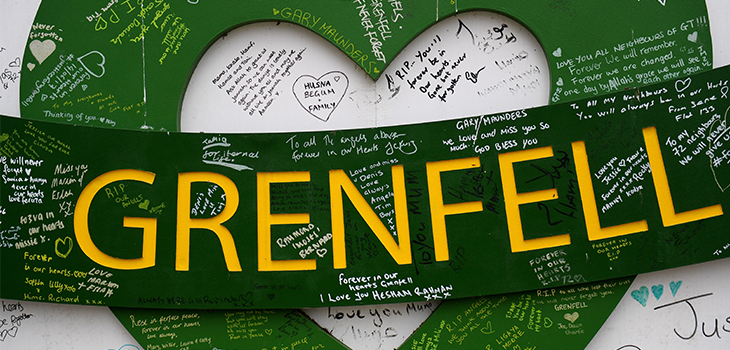

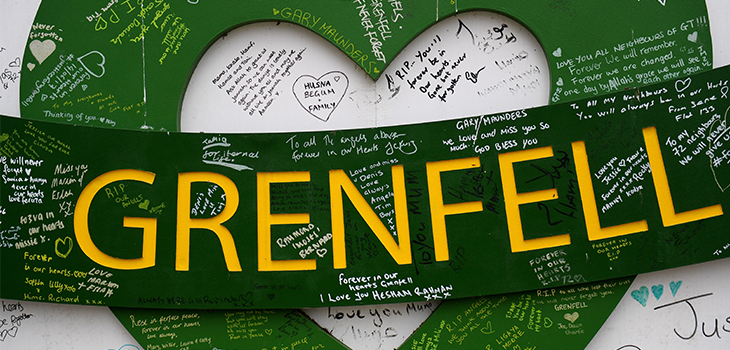

On the fourth anniversary of a tragic fire that claimed 72 lives, Sailesh Mehta outlines four key lessons

Lesson 1: Corporations are greedy and put profit before people

Lesson 2: Public bodies often fail the public

Lesson 3: The poor suffer disproportionately

Lesson 4: Nothing changes (until the public demands change)

The story of Grenfell Tower’s cladding is a story of corporate greed and repeated institutional failure. The residents were let down at each stage of a process designed to protect them.

The Inquiry heard that before the fire, there had been 20 serious fires internationally, involving cladding similar to that used at Grenfell Tower. It was well known in the industry, particularly after seven fires in towers in the UAE between 2012 and 2016, that plastic-filled aluminium panels were highly combustible. The firm that sold the panels knew that they were far more combustible, released seven times as much heat and three times the rate of smoke compared to more expensive panels. Damning fire test results for these panels were not provided to Kensington and Chelsea Council – the company denied deliberate concealment of these results but accepted that the test results supplied were a misleading half-truth. But the council decided to save cost and opted for the cheaper, less safe option.

The residents had approved initial plans for fire resistant zinc cladding but this was later changed by the council to cheaper aluminium cladding with a combustible polyethylene core which residents did not approve, saving nearly £300,000. The council had amassed £274 million of reserves, after years of underspending, and had not used any of its budget surplus to increase fire safety, despite the fact that residents had issued repeated warnings about the Grenfell Tower fire risk. The council actually used the surplus to pay top-rate council taxpayers a £100 rebate shortly before local elections.

A representative of Kensington and Chelsea Council told the Inquiry that building control should have been the ‘last line of defence’ to prevent an unsafe design being built. It admitted that the combustible cladding was wrongly approved by its building control department and that it had made a ‘fundamental failing’ in not asking for detailed information. This was but one of a series of failings including not asking for specific details of the cladding system. These failings led directly to a loss of life. The Inquiry concluded that this cladding actually promoted the spread of the deadly fire.

The volume of calls from distressed residents overwhelmed the Control Room, whose staff had no training in handling such numbers. Each caller in danger should have been given specific information about how to stay safe. But because Control Room staff were not receiving updates from fire fighters, there was no overall plan in prioritising rescues.

The watch manager, amongst the first to arrive at the scene, had no training in how flammable cladding might spread fire so quickly. He was receiving no useful information from the control centre. He had ‘little or no support from more senior officers’ and was let down by institutional failings. The behaviour of the fire was outside his experience and nothing he had done appeared to be having any effect. He was ‘at a loss to understand what was happening or to know how to respond’.

Many high-rise buildings have a ‘stay put’ policy: rather than using the stairs to escape, residents are safer if they remain in their flats and await the fire services who will put out the fire. However, if the compartmentation is breached, then evacuation becomes the safe option. It was clear at an early stage that the fire had breached many compartments and that the residents were in danger if they stayed. Despite this, they were repeatedly told to remain in their flats.

The Inquiry Report found that because of the rapid spread of the fire, the stay put policy should have been abandoned sooner, and more lives could have been saved: ‘The evidence taken as a whole strongly suggests that the “stay put” concept had become an article of faith within the LFB so powerful that to depart from it was to all intents and purposes unthinkable.’

The Chairman of the Inquiry made the following stinging remark about the head of the fire service: ‘Quite apart from its remarkable insensitivity to the families of the deceased and to those who had escaped from their burning homes with their lives, the commissioner's evidence that she would not change anything about the response of the LFB on the night, even with the benefit of hindsight, only serves to demonstrate that the LFB is an institution at risk of not learning the lessons of the Grenfell Tower fire.’

Fire safety regulation in the UK has largely been reactive, only catching up with best practice when there has been another disaster. This approach goes back to the Fire of London and beyond. Experts abroad are staggered that UK legislation allows flammable cladding on high rise blocks, only one staircase as a means of escape, no emergency fire lift for the old and disabled, no requirement for a sprinkler system in older buildings, and an inflexible approach to the ‘stay put’ policy. All of these weaknesses were highlighted by a Coroner after the 2009 Lakanal House Fire and four Ministers were warned repeatedly about the dangers to tower blocks, but little was done.

The Grenfell Tower Inquiry has already unearthed important facts about how the tragedy unfolded and is now engaged in the ‘why did it happen’ questions. This has been necessary for the survivors and the relatives of the deceased, although many of them feel the Inquiry does not go far enough. An alternative view is that the Inquiry is uncovering what everyone knew in advance: that companies who sell products are motivated by greed; that corporations put profit before people; that local authorities, like every modern institution, will cut costs ruthlessly, cut corners, make errors which it will try to hide and react badly when there is a disaster; public bodies such as fire services will continue to be underfunded and become a useful scapegoat when things go badly wrong; and finally, that it always seems to be the poor and powerless who are victims and (as with the Lakanal House Coroner’s Report) nothing will change for some time.

Lesson 1: Corporations are greedy and put profit before people

Lesson 2: Public bodies often fail the public

Lesson 3: The poor suffer disproportionately

Lesson 4: Nothing changes (until the public demands change)

The story of Grenfell Tower’s cladding is a story of corporate greed and repeated institutional failure. The residents were let down at each stage of a process designed to protect them.

The Inquiry heard that before the fire, there had been 20 serious fires internationally, involving cladding similar to that used at Grenfell Tower. It was well known in the industry, particularly after seven fires in towers in the UAE between 2012 and 2016, that plastic-filled aluminium panels were highly combustible. The firm that sold the panels knew that they were far more combustible, released seven times as much heat and three times the rate of smoke compared to more expensive panels. Damning fire test results for these panels were not provided to Kensington and Chelsea Council – the company denied deliberate concealment of these results but accepted that the test results supplied were a misleading half-truth. But the council decided to save cost and opted for the cheaper, less safe option.

The residents had approved initial plans for fire resistant zinc cladding but this was later changed by the council to cheaper aluminium cladding with a combustible polyethylene core which residents did not approve, saving nearly £300,000. The council had amassed £274 million of reserves, after years of underspending, and had not used any of its budget surplus to increase fire safety, despite the fact that residents had issued repeated warnings about the Grenfell Tower fire risk. The council actually used the surplus to pay top-rate council taxpayers a £100 rebate shortly before local elections.

A representative of Kensington and Chelsea Council told the Inquiry that building control should have been the ‘last line of defence’ to prevent an unsafe design being built. It admitted that the combustible cladding was wrongly approved by its building control department and that it had made a ‘fundamental failing’ in not asking for detailed information. This was but one of a series of failings including not asking for specific details of the cladding system. These failings led directly to a loss of life. The Inquiry concluded that this cladding actually promoted the spread of the deadly fire.

The volume of calls from distressed residents overwhelmed the Control Room, whose staff had no training in handling such numbers. Each caller in danger should have been given specific information about how to stay safe. But because Control Room staff were not receiving updates from fire fighters, there was no overall plan in prioritising rescues.

The watch manager, amongst the first to arrive at the scene, had no training in how flammable cladding might spread fire so quickly. He was receiving no useful information from the control centre. He had ‘little or no support from more senior officers’ and was let down by institutional failings. The behaviour of the fire was outside his experience and nothing he had done appeared to be having any effect. He was ‘at a loss to understand what was happening or to know how to respond’.

Many high-rise buildings have a ‘stay put’ policy: rather than using the stairs to escape, residents are safer if they remain in their flats and await the fire services who will put out the fire. However, if the compartmentation is breached, then evacuation becomes the safe option. It was clear at an early stage that the fire had breached many compartments and that the residents were in danger if they stayed. Despite this, they were repeatedly told to remain in their flats.

The Inquiry Report found that because of the rapid spread of the fire, the stay put policy should have been abandoned sooner, and more lives could have been saved: ‘The evidence taken as a whole strongly suggests that the “stay put” concept had become an article of faith within the LFB so powerful that to depart from it was to all intents and purposes unthinkable.’

The Chairman of the Inquiry made the following stinging remark about the head of the fire service: ‘Quite apart from its remarkable insensitivity to the families of the deceased and to those who had escaped from their burning homes with their lives, the commissioner's evidence that she would not change anything about the response of the LFB on the night, even with the benefit of hindsight, only serves to demonstrate that the LFB is an institution at risk of not learning the lessons of the Grenfell Tower fire.’

Fire safety regulation in the UK has largely been reactive, only catching up with best practice when there has been another disaster. This approach goes back to the Fire of London and beyond. Experts abroad are staggered that UK legislation allows flammable cladding on high rise blocks, only one staircase as a means of escape, no emergency fire lift for the old and disabled, no requirement for a sprinkler system in older buildings, and an inflexible approach to the ‘stay put’ policy. All of these weaknesses were highlighted by a Coroner after the 2009 Lakanal House Fire and four Ministers were warned repeatedly about the dangers to tower blocks, but little was done.

The Grenfell Tower Inquiry has already unearthed important facts about how the tragedy unfolded and is now engaged in the ‘why did it happen’ questions. This has been necessary for the survivors and the relatives of the deceased, although many of them feel the Inquiry does not go far enough. An alternative view is that the Inquiry is uncovering what everyone knew in advance: that companies who sell products are motivated by greed; that corporations put profit before people; that local authorities, like every modern institution, will cut costs ruthlessly, cut corners, make errors which it will try to hide and react badly when there is a disaster; public bodies such as fire services will continue to be underfunded and become a useful scapegoat when things go badly wrong; and finally, that it always seems to be the poor and powerless who are victims and (as with the Lakanal House Coroner’s Report) nothing will change for some time.

On the fourth anniversary of a tragic fire that claimed 72 lives, Sailesh Mehta outlines four key lessons

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts