*/

It is sometimes wrongly presumed that ghosts and witches never trespass into the rational jurisdiction of the courts. In time for Halloween, this article looks at two episodes of legal history in which the forensic meets the Fortean, and their impact on the present law.

The Victorians were obsessed with mystery and murder. The proliferation of cheap and gruesome ‘penny dreadful’ pamphlets fuelled widespread fear of Spring Heeled Jack: a fire-breathing demon that allegedly stalked the inner cities. The press turned murderers like Jack the Ripper into celebrity boogeymen, while children sang morbid nursery rhymes about serial poisoner Mary Ann Cotton and suspected axe-murderess Lizzy Borden. However, perhaps the most legally interesting mystery of this bloody century is now the least well known.

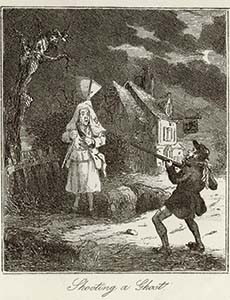

For approximately six weeks during the winter of 1803, Hammersmith residents were terrified by a restless spirit. Fear spread quickly, no doubt due to reports that the ghost had scared a pregnant woman to death, and armed men patrolled the streets. This would lead to tragedy on 3 January 1804, when Thomas Millwood started the short walk home from his father’s house. He was wearing his white work overalls, ignoring his family’s warning that he should change to avoid being confused for the dreaded phantom. At the same time, Francis Smith started his ghost patrol, armed with a pistol. On coming across Millwood on the dark street, Smith shouted, ‘What are you?’ before shooting Millwood dead.

Smith stood trial for murder a mere eight days after the shooting, and the Hammersmith ghost mystery was at the heart of his defence. Smith argued that he had no intention to kill a person, but had used reasonable force to protect himself from a perceived supernatural threat. Witnesses described the fear that gripped Hammersmith. One even described being attacked by the ghost when it emerged from behind a gravestone and grabbed him by the throat. However, the judge directed that Smith’s belief was irrelevant because it was not reasonable to construe a man dressed in white overalls as a ghost. After being prevented from returning a verdict of manslaughter, the jury convicted Smith of murder. The judge imposed the mandatory death sentence, but took the unusual step of referring the case to the King, who commuted the sentence to one year’s imprisonment.

It took 180 years for the law to abandon the requirement that the defendant’s belief had to be genuine and reasonable. The shift started with DPP v Morgan (1975) 61 Cr App R 136, in which the House of Lords concluded (controversially) that a defendant was not guilty of rape if he had a genuine but objectively unreasonable belief in the victim’s consent. In 1984, that rationale was applied to self-defence, when the Court of Appeal held that a person could rely on self-defence if they used reasonable force to protect themselves from a threat that they genuinely but unreasonably believed they faced (R v Williams (Gladstone) 78 Cr App R 276). While Parliament would eventually reintroduce the reasonableness requirement to rape, it remains absent from self-defence (s 76 of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008).

The spiritualist movement started in New York State in the 1840s. Sudden outbreaks of religious fervour were so common in that area that it became known as the ‘burned over district’. The invention of photography lent the movement a veneer of scientific legitimacy as it allowed mediums to produce ‘evidence’ of their abilities. Moreover, spiritualism thrived during periods of mass tragedy. For these reasons, its popularity exploded during the Second World War. The war would also lead to the downfall of one popular medium, Helen Duncan.

In January 1944, two navy officers and an undercover police officer attended Duncan’s ‘temple’ to observe two séances. On both occasions, Duncan took her place inside a ‘medium’s cabinet’ – a large box with a curtain across the front. Through the curtain, a featureless white male face emerged and greeted the crowd of spectators. This was Albert, Duncan’s spirit guide. In addition to sharing messages from the spirit world, Albert released a cat and a parrot from the cabinet, allegedly spirits of long deceased friends and relatives, while ectoplasm poured from Duncan’s mouth. The scenes, which arguably belonged in a Noel Coward farce, ended with the police officer grabbing an apparent ghost, only to discover that it was Duncan.

She was initially charged with pretending to use any ‘subtle craft’ to deceive His Majesty’s subjects, contrary to the Vagrancy Act 1824. However, Duncan would stand trial at the Central Criminal Court for conspiring with others to pretend to be involved in the conjuration of spirits, contrary to the Witchcraft Act 1735. It would be one of the final prosecutions under this ancient Act. Despite its arcane name, the Act was actually an attempt to modernise; unlike its predecessors, it sought to punish those who pretended to conjure spirits. Duncan’s defence was simple – she was not pretending. She called myriad witnesses to testify that she was a genuine medium, but it was not enough to persuade the jury. She was convicted and sentenced to nine months’ imprisonment.

In Duncan’s appeal, the Court of Appeal considered two of the strangest appeal points in legal history ([1944] KB 714). Did the judge err in refusing to allow her to perform a séance to the jury to prove she was genuine? The court quickly disposed of that argument, but not before musing on the practicalities. What was to be done with the ectoplasm? Should the jury be allowed to examine it? Even if those issues could be remedied, such a performance would only have served to confuse the jury.

The second ground concerned statutory interpretation. Historically, witchcraft legislation prohibited communicating with ‘evil’ spirits. Indeed, counsel for Duncan suggested that ‘conjuration’ had a well-defined legal meaning, namely communing with the devil or evil spirits. There was no evidence that the spirits in this case were evil. The court described the argument rather euphemistically as ‘interesting and elaborate’, before concluding that the 1735 Act omitted any reference to ‘evil spirits’ because it was concerned with those who exploited or defrauded ‘ignorant persons’, rather than actual witches.

Duncan’s conviction was upheld, but one mystery remains. Why was the Witchcraft Act preferred over the summary only offence in the Vagrancy Act 1824? Winston Churchill described the prosecution as ‘obsolete tomfoolery, to the detriment of the necessary work in the court’. Despite this comment, it has occasionally been speculated that the prosecution was politically motivated. On 24 November 1941, the HMS Barham sank after being torpedoed by a German Submarine. Next of kin were informed, but it was not widely reported. Therefore, legend has it, the Ministry of Defence and Security Services must have been spooked to hear reports that Duncan had communed with the spirit of a sailor killed on the ship. Fearing that she was a real witch, or more likely, a real spy, they assisted in the investigation and prosecution. However, this allegation was never explored at trial, and one has to wonder why they waited until 1944 to launch an investigation if their concerns were so severe.

Duncan’s conviction did leave a legacy. Her prosecution outraged the spiritualist community and following a campaign spearheaded by the Labour MP and practising spiritualist Thomas Brooks, the Witchcraft Act 1735 was replaced by the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951. In an attempt to distinguish between frauds and ‘genuine’ mediums, the Act permitted the performing of ‘telepathy, clairvoyance or other similar powers’ for the purpose of entertainment. Mediums were rarely prosecuted, and the Act has since been replaced by the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008.

The popular medium Helen Duncan (R), the last woman convicted under the Witchcraft Act 1735 in 1944, pictured ‘emitting’ ecotoplasm in her medium’s cabinet (L). A contemporary newspaper report can be viewed online (National Archives HO 144/22172).

It is sometimes wrongly presumed that ghosts and witches never trespass into the rational jurisdiction of the courts. In time for Halloween, this article looks at two episodes of legal history in which the forensic meets the Fortean, and their impact on the present law.

The Victorians were obsessed with mystery and murder. The proliferation of cheap and gruesome ‘penny dreadful’ pamphlets fuelled widespread fear of Spring Heeled Jack: a fire-breathing demon that allegedly stalked the inner cities. The press turned murderers like Jack the Ripper into celebrity boogeymen, while children sang morbid nursery rhymes about serial poisoner Mary Ann Cotton and suspected axe-murderess Lizzy Borden. However, perhaps the most legally interesting mystery of this bloody century is now the least well known.

For approximately six weeks during the winter of 1803, Hammersmith residents were terrified by a restless spirit. Fear spread quickly, no doubt due to reports that the ghost had scared a pregnant woman to death, and armed men patrolled the streets. This would lead to tragedy on 3 January 1804, when Thomas Millwood started the short walk home from his father’s house. He was wearing his white work overalls, ignoring his family’s warning that he should change to avoid being confused for the dreaded phantom. At the same time, Francis Smith started his ghost patrol, armed with a pistol. On coming across Millwood on the dark street, Smith shouted, ‘What are you?’ before shooting Millwood dead.

Smith stood trial for murder a mere eight days after the shooting, and the Hammersmith ghost mystery was at the heart of his defence. Smith argued that he had no intention to kill a person, but had used reasonable force to protect himself from a perceived supernatural threat. Witnesses described the fear that gripped Hammersmith. One even described being attacked by the ghost when it emerged from behind a gravestone and grabbed him by the throat. However, the judge directed that Smith’s belief was irrelevant because it was not reasonable to construe a man dressed in white overalls as a ghost. After being prevented from returning a verdict of manslaughter, the jury convicted Smith of murder. The judge imposed the mandatory death sentence, but took the unusual step of referring the case to the King, who commuted the sentence to one year’s imprisonment.

It took 180 years for the law to abandon the requirement that the defendant’s belief had to be genuine and reasonable. The shift started with DPP v Morgan (1975) 61 Cr App R 136, in which the House of Lords concluded (controversially) that a defendant was not guilty of rape if he had a genuine but objectively unreasonable belief in the victim’s consent. In 1984, that rationale was applied to self-defence, when the Court of Appeal held that a person could rely on self-defence if they used reasonable force to protect themselves from a threat that they genuinely but unreasonably believed they faced (R v Williams (Gladstone) 78 Cr App R 276). While Parliament would eventually reintroduce the reasonableness requirement to rape, it remains absent from self-defence (s 76 of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008).

The spiritualist movement started in New York State in the 1840s. Sudden outbreaks of religious fervour were so common in that area that it became known as the ‘burned over district’. The invention of photography lent the movement a veneer of scientific legitimacy as it allowed mediums to produce ‘evidence’ of their abilities. Moreover, spiritualism thrived during periods of mass tragedy. For these reasons, its popularity exploded during the Second World War. The war would also lead to the downfall of one popular medium, Helen Duncan.

In January 1944, two navy officers and an undercover police officer attended Duncan’s ‘temple’ to observe two séances. On both occasions, Duncan took her place inside a ‘medium’s cabinet’ – a large box with a curtain across the front. Through the curtain, a featureless white male face emerged and greeted the crowd of spectators. This was Albert, Duncan’s spirit guide. In addition to sharing messages from the spirit world, Albert released a cat and a parrot from the cabinet, allegedly spirits of long deceased friends and relatives, while ectoplasm poured from Duncan’s mouth. The scenes, which arguably belonged in a Noel Coward farce, ended with the police officer grabbing an apparent ghost, only to discover that it was Duncan.

She was initially charged with pretending to use any ‘subtle craft’ to deceive His Majesty’s subjects, contrary to the Vagrancy Act 1824. However, Duncan would stand trial at the Central Criminal Court for conspiring with others to pretend to be involved in the conjuration of spirits, contrary to the Witchcraft Act 1735. It would be one of the final prosecutions under this ancient Act. Despite its arcane name, the Act was actually an attempt to modernise; unlike its predecessors, it sought to punish those who pretended to conjure spirits. Duncan’s defence was simple – she was not pretending. She called myriad witnesses to testify that she was a genuine medium, but it was not enough to persuade the jury. She was convicted and sentenced to nine months’ imprisonment.

In Duncan’s appeal, the Court of Appeal considered two of the strangest appeal points in legal history ([1944] KB 714). Did the judge err in refusing to allow her to perform a séance to the jury to prove she was genuine? The court quickly disposed of that argument, but not before musing on the practicalities. What was to be done with the ectoplasm? Should the jury be allowed to examine it? Even if those issues could be remedied, such a performance would only have served to confuse the jury.

The second ground concerned statutory interpretation. Historically, witchcraft legislation prohibited communicating with ‘evil’ spirits. Indeed, counsel for Duncan suggested that ‘conjuration’ had a well-defined legal meaning, namely communing with the devil or evil spirits. There was no evidence that the spirits in this case were evil. The court described the argument rather euphemistically as ‘interesting and elaborate’, before concluding that the 1735 Act omitted any reference to ‘evil spirits’ because it was concerned with those who exploited or defrauded ‘ignorant persons’, rather than actual witches.

Duncan’s conviction was upheld, but one mystery remains. Why was the Witchcraft Act preferred over the summary only offence in the Vagrancy Act 1824? Winston Churchill described the prosecution as ‘obsolete tomfoolery, to the detriment of the necessary work in the court’. Despite this comment, it has occasionally been speculated that the prosecution was politically motivated. On 24 November 1941, the HMS Barham sank after being torpedoed by a German Submarine. Next of kin were informed, but it was not widely reported. Therefore, legend has it, the Ministry of Defence and Security Services must have been spooked to hear reports that Duncan had communed with the spirit of a sailor killed on the ship. Fearing that she was a real witch, or more likely, a real spy, they assisted in the investigation and prosecution. However, this allegation was never explored at trial, and one has to wonder why they waited until 1944 to launch an investigation if their concerns were so severe.

Duncan’s conviction did leave a legacy. Her prosecution outraged the spiritualist community and following a campaign spearheaded by the Labour MP and practising spiritualist Thomas Brooks, the Witchcraft Act 1735 was replaced by the Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951. In an attempt to distinguish between frauds and ‘genuine’ mediums, the Act permitted the performing of ‘telepathy, clairvoyance or other similar powers’ for the purpose of entertainment. Mediums were rarely prosecuted, and the Act has since been replaced by the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008.

The popular medium Helen Duncan (R), the last woman convicted under the Witchcraft Act 1735 in 1944, pictured ‘emitting’ ecotoplasm in her medium’s cabinet (L). A contemporary newspaper report can be viewed online (National Archives HO 144/22172).

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts