*/

Unsparing in his criticism, the former Attorney General reflects on recent events in government and his own experience of being chief legal adviser.

Interview by Anthony Inglese CB

‘It was a bad moment when the government’s Internal Markets Bill sought to overwrite parts of the Northern Ireland Protocol. The Attorney General’s explanation about the role of international law was untenable and deeply troubling; her going off for advice from sources that were insufficiently credible was equally untenable. The resignation of the Treasury Solicitor, Sir Jonathan Jones, highlighted the breakdown in the system for providing best advice to government. The fact that the AG remained in post suggests a troubling rift in the system. Sir Jonathan resigned for an entirely correct reason. There was a clear breach of the ministerial code; the code had not been changed; the AG’s explanation of why there had been no breach was untenable; and the Cabinet Secretary apparently felt obliged to bend with the wind. The Prime Minister ignored the code and the AG enabled him to avoid the difficulties of doing this.’

The Right Honourable Dominic Grieve QC, former AG himself and thorn in the government’s side over Brexit, is unsparing in his criticism when we talk in February. ‘I campaigned for the AG [Suella Braverman] when she stood for Parliament. It’s a challenging job. I still remember the moment when in 2010 I accepted PM David Cameron’s request to be AG. Somebody offered to send a car to collect me. I said I’d walk. I needed time to think about the job. When I arrived, the entire office was waiting for me. They wanted me to tell them my policies. Instead I offered my principles: the office was crucial to government; I had lots to learn; I wanted us to be totally professional, our advice to be excellent; we would uphold the rule of law. I received a round of applause! They came together again on the day I left office and I was able to thank them for their great support in doing the job.’

Those who have worked with Dominic Grieve might regard him as born for the role of AG, but on leaving Oxford, where he had taken modern history (‘my great love’), he was in two minds about a career. ‘I wasn’t sure about law. My QC father rightly said the independent, self-employed life at the Bar would suit my temperament. I applied to the Foreign Office but lost out at round two and so went to poly to convert to law. During that cramming year the learning was inevitably a bit sterile – not a period when I was highly motivated. But everything changed after I got pupillage and was able to stand on my feet. Advocacy is a demanding performing art: if you don’t feel the adrenalin rush as you stand up as AG before the Supreme Court, you know it’s not going to work. Can you take complex arguments and reduce them to something intelligible and accurate? I enjoyed the courtroom discussions, jury advocacy, questioning witnesses.

‘As AG I felt very strongly I should be in court, to keep in touch with the profession and professional standards. When you go into court as AG you have considerable support, sometimes from silks, which reduces the anxiety of not being on top of the law or of failing to put points to the court, and you can then concentrate on the presentation. The AG leads a privileged life in that respect!’

His ‘best case’ was the Prisoner Voting case in 2013 before the Supreme Court (Chester and McGeoch). ‘There was an attempt to argue that our legislation which prevented prisoners voting should be struck down under EU law, a prospect which David Cameron had said made him ‘physically ill’ and should be avoided at all costs. We won. The court repeated that the UK remained in breach of the Human Rights Convention but refused the declaration that the claimants had sought. It was a case that was delightful to argue, even having a Scottish element. On the day before the result was to be announced, counsel were invited to read the embargoed judgments but on a counsel-only basis. I couldn’t tell the PM the result, even though later the next day he was taking PM Questions where the case was bound to feature. So next morning I went to No 10, taking a bottle of champagne in a carrier, and was waiting in the PM’s outer office when I heard Big Ben strike 10am, the moment when the embargo ended. The PM opened his door and asked “Well?” I produced the bottle. We had got what we wanted. It was a good moment.

‘On arrival as AG I found that the office had virtually given up trying to control the Press for contempt of court in relation to jury trials. I set out to change that. I took the Sun and Mirror to court for their vilification of Christopher Jefferies in Bristol, though he had not even been charged with the murder of Joanna Yeates. In-house counsel for other newspapers told me they were grateful for what I had done, as it supported their advice to their clients.

‘Advising in Cabinet is a form of gentle advocacy. I had to switch from the expert conversations I enjoyed with government lawyers and counsel to language that would be understood, whilst avoiding coming over as toffee-nosed. It can be irritating when lawyers say no, so one always has to suggest alternatives. I always had to know what was coming up and what was being said in the margins and even the corridor outside!’

There was one moment when Dominic came close to resigning as AG. ‘The government was contemplating doing something seriously unacceptable. It blew up one evening. There was a lot of pushing and shoving. I told my office that my position would be untenable if government did it. They communicated down the line that “the AG may go” and the proposal was dropped later in the evening.’

David Cameron and Dominic Grieve parted in 2014 over ‘a fundamental issue that ultimately was fruitless – the government’s plan to scrap the Human Rights Act and replace it with a British Bill of Rights, with a default position that, if the British version proved unworkable, the UK would derogate from the Human Rights Convention. I thought it a really bad idea, completely pointless. The PM knew what I thought. So I was replaced as AG. The proposal found its way into the 2015 manifesto but low down, and it never happened. I accept that the Human Rights Act can be seen as irksome, but it is far better to work with it than find ways to work around it; and our judiciary are now more confident and proactive in challenging the jurisprudence of the Human Rights Court.’

Dominic’s European outlook began in his cradle, his mother half French, her father a French army officer in WW1. ‘She was brought up in Paris in an Anglo-French environment and spoke flawless English. She enjoyed a career in the civil service, including at the then Monopolies and Mergers Commission, until her marriage, and these days would have gone on to have a full career in public service. I was brought up to be bilingual, my mother speaking to me mostly in French in my early years and always scolding me in French. I attended the Lycée Francais in South Kensington and enjoyed holidays in France, conversing in French and reading French literature. My father was a Francophile and Francophone. He had been called to the Bar before WW2, then served as a staff officer and worked on the Liberation of Luxemburg and war crimes trials in 1945-6, returning to the Bar, taking silk and entering Parliament in 1964. He was thrilled when I was elected in 1997. Although by then in his 80s, he stayed up all night for the count and was buoyant all next day.’

As a highly effective Brexit rebel, Dominic lost his seat in 2019 when he stood in the December General Election as an independent, after his expulsion from the Conservative party. But Brexit has happened. So, was it all worth it? ‘I voted for the referendum. I regret it now! I had no Machiavellian desire to stop Brexit but I questioned whether people would still feel they wanted Brexit when we got to the point. I was horrified by the attacks on the judiciary over Article 50. The draconian Henry VIII powers in the Withdrawal Act occasioned my first rebellion; later I was very concerned by proposals that marginalised the role of Parliament and by the fact that the Brexit that was then on offer was different from what was originally mooted. I felt we needed a second referendum. Politics is a difficult business. I couldn’t look myself in the eye if I hadn’t taken the stand I did as a Parliamentarian. And there were some high points, for example seeing off the PM’s intention to get us out without proper preparation on 31 October 2019.’

Is there a sense of having been cast adrift? ‘No. I have resumed my practice at Temple Garden Chambers; I am enjoying being a trustee of charities, being on the periphery of politics, doing webinars on human rights, Brexit, intelligence and security and being a visiting professor at Goldsmiths; and I should like to add more to the mix. COVID has made things more complicated…’

Advice for those on the threshold of law? ‘If you have an interest outside of law, look at universities that combine law with other subjects; if money is less of an issue, think about studying another subject and converting to law afterwards. There are many interesting roles for lawyers: government, in-house, big and small law firms, not for profit – and, of course, the Bar. Decide honestly where your skills and ambitions lie. People mature differently; skills emerge later.

‘The Bar offers opportunities for people of academic ability and with advocacy skills; it is highly competitive; but it is recognising hard truths. It has expanded enormously since I started out in 1980. There was lots of work available, some of it publicly funded, not well paid and now come to an end. Today’s Bar struggles with insufficient work of proper quality for those going into it. If you have applied to the wrong chambers for your skills, you will face serious difficulties. The bonanza period won’t come back.’

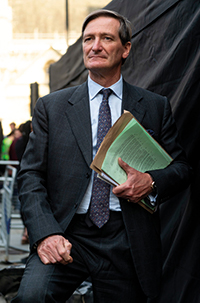

Dominic Grieve QC (pictured above preparing to speak at an anti-Brexit rally in Parliament Square in September 2019) was MP for Beaconsfield from 1997 to 2019; Attorney General in the Coalition Government from 2010-2014; Chair of the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament from 2015 to 2019; and in 2010 was appointed a Privy Councillor.

‘It was a bad moment when the government’s Internal Markets Bill sought to overwrite parts of the Northern Ireland Protocol. The Attorney General’s explanation about the role of international law was untenable and deeply troubling; her going off for advice from sources that were insufficiently credible was equally untenable. The resignation of the Treasury Solicitor, Sir Jonathan Jones, highlighted the breakdown in the system for providing best advice to government. The fact that the AG remained in post suggests a troubling rift in the system. Sir Jonathan resigned for an entirely correct reason. There was a clear breach of the ministerial code; the code had not been changed; the AG’s explanation of why there had been no breach was untenable; and the Cabinet Secretary apparently felt obliged to bend with the wind. The Prime Minister ignored the code and the AG enabled him to avoid the difficulties of doing this.’

The Right Honourable Dominic Grieve QC, former AG himself and thorn in the government’s side over Brexit, is unsparing in his criticism when we talk in February. ‘I campaigned for the AG [Suella Braverman] when she stood for Parliament. It’s a challenging job. I still remember the moment when in 2010 I accepted PM David Cameron’s request to be AG. Somebody offered to send a car to collect me. I said I’d walk. I needed time to think about the job. When I arrived, the entire office was waiting for me. They wanted me to tell them my policies. Instead I offered my principles: the office was crucial to government; I had lots to learn; I wanted us to be totally professional, our advice to be excellent; we would uphold the rule of law. I received a round of applause! They came together again on the day I left office and I was able to thank them for their great support in doing the job.’

Those who have worked with Dominic Grieve might regard him as born for the role of AG, but on leaving Oxford, where he had taken modern history (‘my great love’), he was in two minds about a career. ‘I wasn’t sure about law. My QC father rightly said the independent, self-employed life at the Bar would suit my temperament. I applied to the Foreign Office but lost out at round two and so went to poly to convert to law. During that cramming year the learning was inevitably a bit sterile – not a period when I was highly motivated. But everything changed after I got pupillage and was able to stand on my feet. Advocacy is a demanding performing art: if you don’t feel the adrenalin rush as you stand up as AG before the Supreme Court, you know it’s not going to work. Can you take complex arguments and reduce them to something intelligible and accurate? I enjoyed the courtroom discussions, jury advocacy, questioning witnesses.

‘As AG I felt very strongly I should be in court, to keep in touch with the profession and professional standards. When you go into court as AG you have considerable support, sometimes from silks, which reduces the anxiety of not being on top of the law or of failing to put points to the court, and you can then concentrate on the presentation. The AG leads a privileged life in that respect!’

His ‘best case’ was the Prisoner Voting case in 2013 before the Supreme Court (Chester and McGeoch). ‘There was an attempt to argue that our legislation which prevented prisoners voting should be struck down under EU law, a prospect which David Cameron had said made him ‘physically ill’ and should be avoided at all costs. We won. The court repeated that the UK remained in breach of the Human Rights Convention but refused the declaration that the claimants had sought. It was a case that was delightful to argue, even having a Scottish element. On the day before the result was to be announced, counsel were invited to read the embargoed judgments but on a counsel-only basis. I couldn’t tell the PM the result, even though later the next day he was taking PM Questions where the case was bound to feature. So next morning I went to No 10, taking a bottle of champagne in a carrier, and was waiting in the PM’s outer office when I heard Big Ben strike 10am, the moment when the embargo ended. The PM opened his door and asked “Well?” I produced the bottle. We had got what we wanted. It was a good moment.

‘On arrival as AG I found that the office had virtually given up trying to control the Press for contempt of court in relation to jury trials. I set out to change that. I took the Sun and Mirror to court for their vilification of Christopher Jefferies in Bristol, though he had not even been charged with the murder of Joanna Yeates. In-house counsel for other newspapers told me they were grateful for what I had done, as it supported their advice to their clients.

‘Advising in Cabinet is a form of gentle advocacy. I had to switch from the expert conversations I enjoyed with government lawyers and counsel to language that would be understood, whilst avoiding coming over as toffee-nosed. It can be irritating when lawyers say no, so one always has to suggest alternatives. I always had to know what was coming up and what was being said in the margins and even the corridor outside!’

There was one moment when Dominic came close to resigning as AG. ‘The government was contemplating doing something seriously unacceptable. It blew up one evening. There was a lot of pushing and shoving. I told my office that my position would be untenable if government did it. They communicated down the line that “the AG may go” and the proposal was dropped later in the evening.’

David Cameron and Dominic Grieve parted in 2014 over ‘a fundamental issue that ultimately was fruitless – the government’s plan to scrap the Human Rights Act and replace it with a British Bill of Rights, with a default position that, if the British version proved unworkable, the UK would derogate from the Human Rights Convention. I thought it a really bad idea, completely pointless. The PM knew what I thought. So I was replaced as AG. The proposal found its way into the 2015 manifesto but low down, and it never happened. I accept that the Human Rights Act can be seen as irksome, but it is far better to work with it than find ways to work around it; and our judiciary are now more confident and proactive in challenging the jurisprudence of the Human Rights Court.’

Dominic’s European outlook began in his cradle, his mother half French, her father a French army officer in WW1. ‘She was brought up in Paris in an Anglo-French environment and spoke flawless English. She enjoyed a career in the civil service, including at the then Monopolies and Mergers Commission, until her marriage, and these days would have gone on to have a full career in public service. I was brought up to be bilingual, my mother speaking to me mostly in French in my early years and always scolding me in French. I attended the Lycée Francais in South Kensington and enjoyed holidays in France, conversing in French and reading French literature. My father was a Francophile and Francophone. He had been called to the Bar before WW2, then served as a staff officer and worked on the Liberation of Luxemburg and war crimes trials in 1945-6, returning to the Bar, taking silk and entering Parliament in 1964. He was thrilled when I was elected in 1997. Although by then in his 80s, he stayed up all night for the count and was buoyant all next day.’

As a highly effective Brexit rebel, Dominic lost his seat in 2019 when he stood in the December General Election as an independent, after his expulsion from the Conservative party. But Brexit has happened. So, was it all worth it? ‘I voted for the referendum. I regret it now! I had no Machiavellian desire to stop Brexit but I questioned whether people would still feel they wanted Brexit when we got to the point. I was horrified by the attacks on the judiciary over Article 50. The draconian Henry VIII powers in the Withdrawal Act occasioned my first rebellion; later I was very concerned by proposals that marginalised the role of Parliament and by the fact that the Brexit that was then on offer was different from what was originally mooted. I felt we needed a second referendum. Politics is a difficult business. I couldn’t look myself in the eye if I hadn’t taken the stand I did as a Parliamentarian. And there were some high points, for example seeing off the PM’s intention to get us out without proper preparation on 31 October 2019.’

Is there a sense of having been cast adrift? ‘No. I have resumed my practice at Temple Garden Chambers; I am enjoying being a trustee of charities, being on the periphery of politics, doing webinars on human rights, Brexit, intelligence and security and being a visiting professor at Goldsmiths; and I should like to add more to the mix. COVID has made things more complicated…’

Advice for those on the threshold of law? ‘If you have an interest outside of law, look at universities that combine law with other subjects; if money is less of an issue, think about studying another subject and converting to law afterwards. There are many interesting roles for lawyers: government, in-house, big and small law firms, not for profit – and, of course, the Bar. Decide honestly where your skills and ambitions lie. People mature differently; skills emerge later.

‘The Bar offers opportunities for people of academic ability and with advocacy skills; it is highly competitive; but it is recognising hard truths. It has expanded enormously since I started out in 1980. There was lots of work available, some of it publicly funded, not well paid and now come to an end. Today’s Bar struggles with insufficient work of proper quality for those going into it. If you have applied to the wrong chambers for your skills, you will face serious difficulties. The bonanza period won’t come back.’

Dominic Grieve QC (pictured above preparing to speak at an anti-Brexit rally in Parliament Square in September 2019) was MP for Beaconsfield from 1997 to 2019; Attorney General in the Coalition Government from 2010-2014; Chair of the Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament from 2015 to 2019; and in 2010 was appointed a Privy Councillor.

Unsparing in his criticism, the former Attorney General reflects on recent events in government and his own experience of being chief legal adviser.

Interview by Anthony Inglese CB

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts