*/

With extremist views becoming more commonplace, is the law keeping up? Leila Taleb examines the increasingly uneasy balance between freedom of expressoin and protected characteristics

I wrote an article recently which discussed the balancing of gender-critical views with trans-gender rights in the context of employment law, with specific reference to the case of Forstater v CGD Europe UKEAT/0105/20/JOJ. This article hopes to ignite a discussion of the conflict between the freedom of expression and particular expressions/beliefs that harm particular groups, and what it could mean for the law and society moving forwards.

The boundary between article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) (freedom of expression) and what constitutes being offensive/degrading to particular groups is increasingly arising in people’s private lives, at school, employment disciplinaries and particularly social media where beliefs are regularly expounded about whether a woman can ever become a man and vice versa; that COVID-19 or climate change is a conspiracy; particular genocides/acts of war never took place; homosexuality is contrary to God’s law; that women are designed to take care of men and the home.

In criminal law, behaviour and the expression of views need to be of a threshold that satisfies criminal culpability. Hate crime is behaviour which demonstrates hostility, hatred or bias towards a particular group in society. There are a number of other offences available to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) when punishing the actioning and/or airing of such harmful beliefs, such as offences known as ‘communication offences’. These can include: sending a communication that is indecent or grossly offensive; or sending a communication over a public electronic communications network that is grossly offensive or of indecent, obscene or menacing character.

The communication has to be ‘grossly offensive’ or ‘indecent’ as interpreted in the ordinary sense of the word. In DPP v Colins [2006] UKHL 40, the defendant made racially offensive telephone calls to the officers of his Member of Parliament and left racially offensive telephone messages. The issue was whether the magistrates had erred in finding that the defendant was not guilty of the offence as they did not believe these comments were ‘grossly offensive’. The High Court indicated that grossly offensive must apply to the contemporary standards of an open and just multi-racial society and the words must be judged taking account of their context and all relevant circumstances. ‘Grossly offensive’ required something ‘beyond the pale of what is tolerable in our society’ thus preserving the right to ‘express opinions that offend, shock or disturb the state or any section of the population’. This judgment attempted to balance the competing rights of article 10 (freedom of expression) and article 8 (right to private life). I am in no doubt that if such a case came to the courts today, the magistrates would have come to a different conclusion.

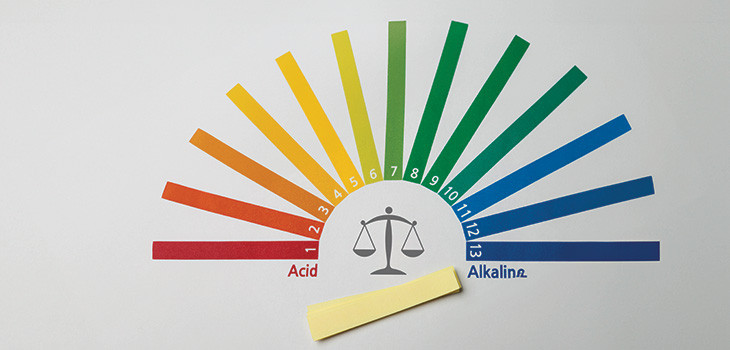

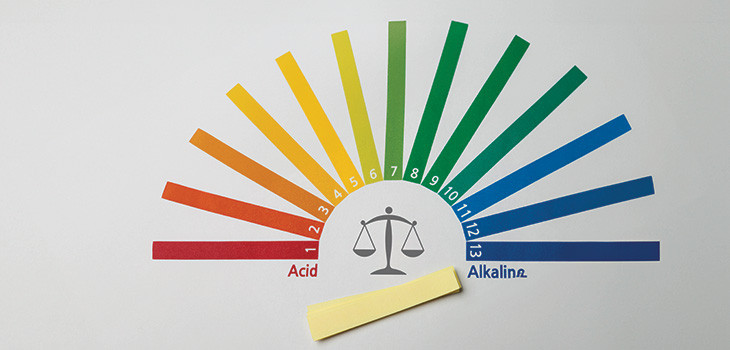

The litmus test for the perfect balance often depends on what political party one supports, what one’s own protected characteristics are, what religion one follows amongst other facets of one’s identity. Nonetheless, as society moves in a direction which encompasses increasing diversity, the litmus test rears its head more acutely when a large proportion of society is not ready to concede a particular ‘belief’.

Should society simply be more tolerant of varying beliefs? Are people’s views becoming more extreme? Does an increase in diversity mean an increase in a spectrum of beliefs that can clash with the freedom of expression? How do we deal with this? Is it the case that we are becoming less tolerant because of the echo chambers of social media? Is society moving at the same rate as the legal landscape? If views are becoming more extreme, then how do we protect particular groups that are in need of protection?

The test for what constitutes a belief worthy of protection in employment law under the Equality Act is contained in Grainger Plc & Ors v Nicholson [2009] UKEAT 0219_09_0311. The belief must be genuinely held; it must be a belief based on the present state of information available; it must be a belief as to a weight and substantial aspect of human life and behaviour; it must attain a certain level of cogency, seriousness, cohesion and importance; it must be worthy of respect in a democratic society and not be incompatible with human dignity and not conflict with the fundamental rights of others.

One particular ‘belief’ that some parts of society have not been ready to accept is the belief that gender is fluid. The fluidity of gender and the recognition of different gender identities is something that society has been confronted with over more recent years.

There have been varying degrees of dissent within our courts on this topic which is often a reflection of the same division on the topic across society.

There was the case of Forstater. There is the recent case of Bailey v Stonewall and Garden Court Chambers Case No: 2202172/2020 concerning a claimant holding gender-critical views on social media and damaging her chamber’s reputation. The ET held that she was discriminated against by her chambers. There is also Mackereth v DWP [2022] EAT 99, whereby the EAT held that implementing a policy requiring a doctor to address transgender service users using pronouns of their ‘presented gender’ was objectively justified. Application of the policy was not indirectly discriminatory, despite the doctor’s assertion that this contradicted his religious beliefs. In Higgs v Farmor’s School [2022] EAT 101 an ET held that a school had not directly discriminated against its former employee when they dismissed her for posting posts on Facebook that ‘might reasonable lead people who read her posts to conclude that she was homophobic and transphobic’ in the ET’s words. Her appeal was upheld and the case has since been remitted back to the ET.

There cannot be a narrowing of what constitutes a ‘protected characteristic’. Those are clearly defined and exist for a reason: they require protection in law particularly at a time where hate crime is at its highest. If anything, the scope and number of current protected characteristics may widen in the future as society aims to become increasingly inclusive.

One example in terms of the way the Equality Act may widen its scope could be the identification of ‘class’ as a protected characteristic. Considering class is indicative of one’s socio-economic status, it inevitably has an impact on one’s opportunities or lack thereof and arguably should be something that is protected in law. If ‘class’ were to be something protected under the Equality Act, it may become increasingly complicated to decide cases of discrimination, which are based on an intersection of a number of different protected characteristics. Often it is not just one protected characteristic on its own but an interplay of more than one that can lead to someone being treated differently.

As the net of protected characteristics widens, there will be undoubtedly an increase in clashes with beliefs that may challenge the pursuit and/or identity of the rights of those particular groups.

Paradoxically the definition of what constitutes a ‘belief’ under the Equality Act includes the requirement that it should not conflict with the fundamental rights of others as per criterion 5 of the Grainger test. This is arguably unattainable in light of the conflicts this article has highlighted. Any belief that questions the premise behind the existence of a particular group of people will surely always breach their rights when interpreted literally. However, the interpretation of this has been a liberal and flexible one as under the case of Forstater. The interpretation of ‘philosophical belief’ under the Equality Act will no doubt be something that courts continue to grapple with.

It ought to be reiterated that while this article has focused on the iteration and existence of beliefs, there are remedies if a particular offence occurs or if the belief is manifested/acted upon.

What may be interesting in due course is how the rise in extreme views may influence the interpretation of how wide we cast our net when defining what beliefs should be worthy of protection. One example being the rise in Andrew Tate and his widely considered misogynistic views, some of which are now harrowingly becoming more widespread particularly among younger male generations. If such views become more widespread, will that shift society and the law’s interpretation of what is a ‘grossly offensive’ view or one that fundamentally disrupts the rights of protected groups? How will such regressive views reconcile with the view that gender is fluid?

The law stands to balance the protection of particular groups against the qualified right of the freedom to express oneself. There is an inevitable continuum between society and law, with both of them influencing one another. If society’s approach to a particular ‘belief’ remains divided, then the application of the law will continue to reap those divisions.

I wrote an article recently which discussed the balancing of gender-critical views with trans-gender rights in the context of employment law, with specific reference to the case of Forstater v CGD Europe UKEAT/0105/20/JOJ. This article hopes to ignite a discussion of the conflict between the freedom of expression and particular expressions/beliefs that harm particular groups, and what it could mean for the law and society moving forwards.

The boundary between article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) (freedom of expression) and what constitutes being offensive/degrading to particular groups is increasingly arising in people’s private lives, at school, employment disciplinaries and particularly social media where beliefs are regularly expounded about whether a woman can ever become a man and vice versa; that COVID-19 or climate change is a conspiracy; particular genocides/acts of war never took place; homosexuality is contrary to God’s law; that women are designed to take care of men and the home.

In criminal law, behaviour and the expression of views need to be of a threshold that satisfies criminal culpability. Hate crime is behaviour which demonstrates hostility, hatred or bias towards a particular group in society. There are a number of other offences available to the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) when punishing the actioning and/or airing of such harmful beliefs, such as offences known as ‘communication offences’. These can include: sending a communication that is indecent or grossly offensive; or sending a communication over a public electronic communications network that is grossly offensive or of indecent, obscene or menacing character.

The communication has to be ‘grossly offensive’ or ‘indecent’ as interpreted in the ordinary sense of the word. In DPP v Colins [2006] UKHL 40, the defendant made racially offensive telephone calls to the officers of his Member of Parliament and left racially offensive telephone messages. The issue was whether the magistrates had erred in finding that the defendant was not guilty of the offence as they did not believe these comments were ‘grossly offensive’. The High Court indicated that grossly offensive must apply to the contemporary standards of an open and just multi-racial society and the words must be judged taking account of their context and all relevant circumstances. ‘Grossly offensive’ required something ‘beyond the pale of what is tolerable in our society’ thus preserving the right to ‘express opinions that offend, shock or disturb the state or any section of the population’. This judgment attempted to balance the competing rights of article 10 (freedom of expression) and article 8 (right to private life). I am in no doubt that if such a case came to the courts today, the magistrates would have come to a different conclusion.

The litmus test for the perfect balance often depends on what political party one supports, what one’s own protected characteristics are, what religion one follows amongst other facets of one’s identity. Nonetheless, as society moves in a direction which encompasses increasing diversity, the litmus test rears its head more acutely when a large proportion of society is not ready to concede a particular ‘belief’.

Should society simply be more tolerant of varying beliefs? Are people’s views becoming more extreme? Does an increase in diversity mean an increase in a spectrum of beliefs that can clash with the freedom of expression? How do we deal with this? Is it the case that we are becoming less tolerant because of the echo chambers of social media? Is society moving at the same rate as the legal landscape? If views are becoming more extreme, then how do we protect particular groups that are in need of protection?

The test for what constitutes a belief worthy of protection in employment law under the Equality Act is contained in Grainger Plc & Ors v Nicholson [2009] UKEAT 0219_09_0311. The belief must be genuinely held; it must be a belief based on the present state of information available; it must be a belief as to a weight and substantial aspect of human life and behaviour; it must attain a certain level of cogency, seriousness, cohesion and importance; it must be worthy of respect in a democratic society and not be incompatible with human dignity and not conflict with the fundamental rights of others.

One particular ‘belief’ that some parts of society have not been ready to accept is the belief that gender is fluid. The fluidity of gender and the recognition of different gender identities is something that society has been confronted with over more recent years.

There have been varying degrees of dissent within our courts on this topic which is often a reflection of the same division on the topic across society.

There was the case of Forstater. There is the recent case of Bailey v Stonewall and Garden Court Chambers Case No: 2202172/2020 concerning a claimant holding gender-critical views on social media and damaging her chamber’s reputation. The ET held that she was discriminated against by her chambers. There is also Mackereth v DWP [2022] EAT 99, whereby the EAT held that implementing a policy requiring a doctor to address transgender service users using pronouns of their ‘presented gender’ was objectively justified. Application of the policy was not indirectly discriminatory, despite the doctor’s assertion that this contradicted his religious beliefs. In Higgs v Farmor’s School [2022] EAT 101 an ET held that a school had not directly discriminated against its former employee when they dismissed her for posting posts on Facebook that ‘might reasonable lead people who read her posts to conclude that she was homophobic and transphobic’ in the ET’s words. Her appeal was upheld and the case has since been remitted back to the ET.

There cannot be a narrowing of what constitutes a ‘protected characteristic’. Those are clearly defined and exist for a reason: they require protection in law particularly at a time where hate crime is at its highest. If anything, the scope and number of current protected characteristics may widen in the future as society aims to become increasingly inclusive.

One example in terms of the way the Equality Act may widen its scope could be the identification of ‘class’ as a protected characteristic. Considering class is indicative of one’s socio-economic status, it inevitably has an impact on one’s opportunities or lack thereof and arguably should be something that is protected in law. If ‘class’ were to be something protected under the Equality Act, it may become increasingly complicated to decide cases of discrimination, which are based on an intersection of a number of different protected characteristics. Often it is not just one protected characteristic on its own but an interplay of more than one that can lead to someone being treated differently.

As the net of protected characteristics widens, there will be undoubtedly an increase in clashes with beliefs that may challenge the pursuit and/or identity of the rights of those particular groups.

Paradoxically the definition of what constitutes a ‘belief’ under the Equality Act includes the requirement that it should not conflict with the fundamental rights of others as per criterion 5 of the Grainger test. This is arguably unattainable in light of the conflicts this article has highlighted. Any belief that questions the premise behind the existence of a particular group of people will surely always breach their rights when interpreted literally. However, the interpretation of this has been a liberal and flexible one as under the case of Forstater. The interpretation of ‘philosophical belief’ under the Equality Act will no doubt be something that courts continue to grapple with.

It ought to be reiterated that while this article has focused on the iteration and existence of beliefs, there are remedies if a particular offence occurs or if the belief is manifested/acted upon.

What may be interesting in due course is how the rise in extreme views may influence the interpretation of how wide we cast our net when defining what beliefs should be worthy of protection. One example being the rise in Andrew Tate and his widely considered misogynistic views, some of which are now harrowingly becoming more widespread particularly among younger male generations. If such views become more widespread, will that shift society and the law’s interpretation of what is a ‘grossly offensive’ view or one that fundamentally disrupts the rights of protected groups? How will such regressive views reconcile with the view that gender is fluid?

The law stands to balance the protection of particular groups against the qualified right of the freedom to express oneself. There is an inevitable continuum between society and law, with both of them influencing one another. If society’s approach to a particular ‘belief’ remains divided, then the application of the law will continue to reap those divisions.

With extremist views becoming more commonplace, is the law keeping up? Leila Taleb examines the increasingly uneasy balance between freedom of expressoin and protected characteristics

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts