*/

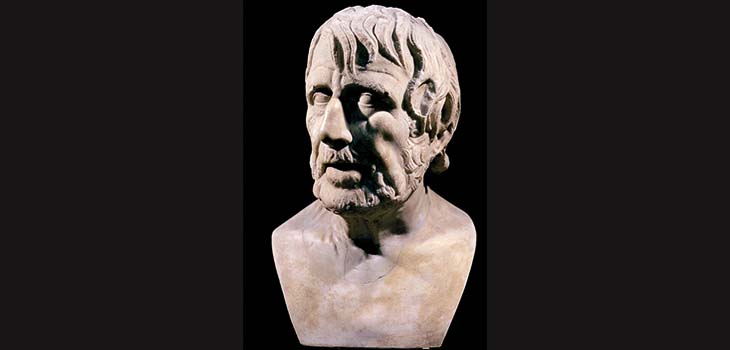

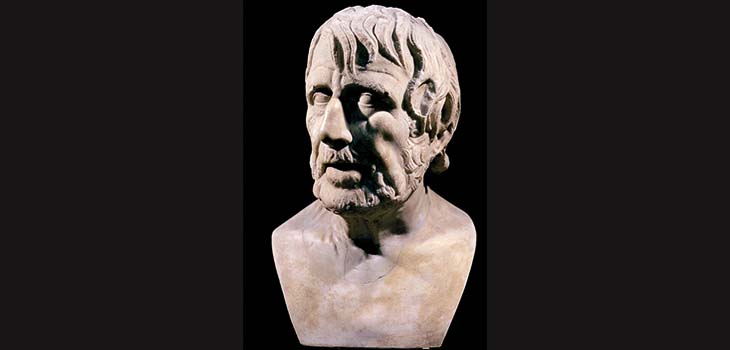

If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favourable.

Wind, like a virus, appears invisible to the human eye. It seems impossible that it can hold the power it does. Today, Paddy Corkhill and I braved one of a series of storms paying us a visit to have lunch together, just as we used to every free Friday in the old days. We chose a tiny restaurant that has somehow survived the modern age with staff who look as if they have walked off the set of Downton Abbey. They swat away any fashionable intrusions. Mobiles definitely off.

An elderly lady sat alone eating a cheese soufflé. We would not have dreamed of interrupting her. She looked as if she had stepped out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, although Paddy pointed out in a whisper that she was in fact a very racy actress in the 1960s. I looked again: I remembered the film that I now knew was in Paddy’s mind. I saw it at home on TV. It is now a cult classic. I wished my parents had not been watching it in the same room. My father and I found we could not look at each other.

‘Seen that thing about abolishing wigs?’ he said. I replied that I had. ‘Sitting here,’ he said, swilling his claret round in a gigantic glass, ‘it gets you angry, doesn’t it?’ ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Thing is,’ said Paddy, ‘do you remember when we were both young barristers and had hair. We each agreed that wigs were utterly ridiculous?’ ‘I certainly remember how annoying I found them,’ I said. ‘What made you change your mind?’ Paddy asked. ‘Probably the effect of aging,’ I replied. Then I changed my mind. ‘No, it isn’t just that. Weirdly, when you are getting on a bit, the wig actually does act as a wig.’ Paddy looked puzzled.

I was thinking of a recent case where a youngish teenage girl was, at her own insistence, giving evidence without special measures before a jury. His Honour Judge Lambray, whom I remember denouncing special measures when they first came in, is now so enthusiastic about them that he nearly forgot himself and became angry with the girl for insisting on not having them.

‘It would be very much better, you know, if you at least had screens,’ he said, in the absence of the jury. ‘I’m fine,’ she said. ‘I want to be able to see the defendant and I want the jury to know that I’m not frightened of him.’ She was a key witness to a near-fatal assault outside a nightclub where, also rather surprisingly given her age, she had been in attendance earlier. ‘I want to be vivid,’ she concluded. I could imagine the secret joy this gave prosecuting counsel despite his well-acted look of concern and the horror of co-defending counsel, to whose defence she was very unhelpful, who was trying less convincingly to look cheerful.

‘Well,’ said the judge to the Bar, ‘I think we should at least remove our wigs.’ We did. Everyone took them off and shook their luxuriant locks, except for me. Even Prosecuting counsel, a man, had an annoying amount of hair. I alone had about as much as Wimbledon Centre Court has blades of grass by the end of the second week. I saw the looks on the faces of the jury when they returned. I had aged 20 years to them. Vanity of vanities; all is vanity. I also remembered university in the early 1970s, a much more revolutionary era than today. We had a huge campaign to get rid of gowns. Then someone pointed out that we always had soup as the first course for dinner (brown, red or yellow), and that in putting it down in front of us, it often splashed our gowns. Without the gowns… The campaign fizzled out in days.

‘Did you find it difficult to walk in the wind today?’ asked Paddy. I had. We had walked over from Chambers to the restaurant. It was so windy I could hardly walk at all at one stage. It was impossible to talk and there was clearly some damage being caused. Dust got into my contact lenses. ‘It’s why they say “winds of change”,’ said Paddy. ‘Wind can damage, it can make you change direction or take shelter ‘til it passes. But it can also be wonderful and invigorating and cleansing.’ The elderly waiter looked at us with some distaste: ‘Will you gentlemen be having the port?’

If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favourable.

Wind, like a virus, appears invisible to the human eye. It seems impossible that it can hold the power it does. Today, Paddy Corkhill and I braved one of a series of storms paying us a visit to have lunch together, just as we used to every free Friday in the old days. We chose a tiny restaurant that has somehow survived the modern age with staff who look as if they have walked off the set of Downton Abbey. They swat away any fashionable intrusions. Mobiles definitely off.

An elderly lady sat alone eating a cheese soufflé. We would not have dreamed of interrupting her. She looked as if she had stepped out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, although Paddy pointed out in a whisper that she was in fact a very racy actress in the 1960s. I looked again: I remembered the film that I now knew was in Paddy’s mind. I saw it at home on TV. It is now a cult classic. I wished my parents had not been watching it in the same room. My father and I found we could not look at each other.

‘Seen that thing about abolishing wigs?’ he said. I replied that I had. ‘Sitting here,’ he said, swilling his claret round in a gigantic glass, ‘it gets you angry, doesn’t it?’ ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Thing is,’ said Paddy, ‘do you remember when we were both young barristers and had hair. We each agreed that wigs were utterly ridiculous?’ ‘I certainly remember how annoying I found them,’ I said. ‘What made you change your mind?’ Paddy asked. ‘Probably the effect of aging,’ I replied. Then I changed my mind. ‘No, it isn’t just that. Weirdly, when you are getting on a bit, the wig actually does act as a wig.’ Paddy looked puzzled.

I was thinking of a recent case where a youngish teenage girl was, at her own insistence, giving evidence without special measures before a jury. His Honour Judge Lambray, whom I remember denouncing special measures when they first came in, is now so enthusiastic about them that he nearly forgot himself and became angry with the girl for insisting on not having them.

‘It would be very much better, you know, if you at least had screens,’ he said, in the absence of the jury. ‘I’m fine,’ she said. ‘I want to be able to see the defendant and I want the jury to know that I’m not frightened of him.’ She was a key witness to a near-fatal assault outside a nightclub where, also rather surprisingly given her age, she had been in attendance earlier. ‘I want to be vivid,’ she concluded. I could imagine the secret joy this gave prosecuting counsel despite his well-acted look of concern and the horror of co-defending counsel, to whose defence she was very unhelpful, who was trying less convincingly to look cheerful.

‘Well,’ said the judge to the Bar, ‘I think we should at least remove our wigs.’ We did. Everyone took them off and shook their luxuriant locks, except for me. Even Prosecuting counsel, a man, had an annoying amount of hair. I alone had about as much as Wimbledon Centre Court has blades of grass by the end of the second week. I saw the looks on the faces of the jury when they returned. I had aged 20 years to them. Vanity of vanities; all is vanity. I also remembered university in the early 1970s, a much more revolutionary era than today. We had a huge campaign to get rid of gowns. Then someone pointed out that we always had soup as the first course for dinner (brown, red or yellow), and that in putting it down in front of us, it often splashed our gowns. Without the gowns… The campaign fizzled out in days.

‘Did you find it difficult to walk in the wind today?’ asked Paddy. I had. We had walked over from Chambers to the restaurant. It was so windy I could hardly walk at all at one stage. It was impossible to talk and there was clearly some damage being caused. Dust got into my contact lenses. ‘It’s why they say “winds of change”,’ said Paddy. ‘Wind can damage, it can make you change direction or take shelter ‘til it passes. But it can also be wonderful and invigorating and cleansing.’ The elderly waiter looked at us with some distaste: ‘Will you gentlemen be having the port?’

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts