*/

On the first anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Mark Guthrie looks at progress on prosecuting Russia’s war crimes and useful lessons to be learnt from the courts of Bosnia and Herzegovina

One year of war in Ukraine has seen the country demonstrate not only its military capacity and resilience, but also its commitment to the rule of law.

As soon as the war began and the nature of the destruction which Russia inflicted on the people of Ukraine became apparent so did discussion of the prosecution of perpetrators of war crimes.

The Prosecutor General of Ukraine began the investigation of war crimes and there has been at least one prosecution of a low-ranking soldier for war crimes. At the international level the International Criminal Court has sent a team to Ukraine and has indicated it is prepared to prosecute war crimes arising out of the conflict. In addition, there has been discussion of establishing a special tribunal to prosecute Russia for the crime of aggression. International assistance has been given to Ukrainian investigators and prosecutors.

However, the reality is that the prosecution on a large scale of the perpetrators of war crimes is unlikely to take place until after the end of the war and upon a significant change in political circumstances.

The fact that Vladimir Putin and senior Russian military officials are in Russia and are likely to remain there is an obstacle to their prosecution. However, that is not to say that Putin and his military leaders will not be prosecuted. It is not impossible that, in the future, circumstances will lead to their prosecution.

This time should be used to devise a strategy as how war crimes committed in Ukraine are investigated and prosecuted effectively and efficiently. There are some useful lessons to be learnt from the investigation and prosecution of war crimes committed during the 1992-95 war in Bosnia Herzegovina.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) attracted much attention for its prosecution of high-profile figures such as Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic. But less well known and recognised has been the role of the courts of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the prosecution of war crimes.

The ICTY transferred some of its cases to the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (the ‘Court BiH’). Since the ICTY completed its case load, the Court BiH has had sole jurisdiction over the prosecution of war crimes. However, it has transferred some of the less complex cases to local courts across the two entities of Bosnia Herzegovina.

Nearly 30 years after the end of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, many war crimes cases have yet to be prosecuted. No one should expect an early end to the investigation and prosecution of war crimes arising out of the Ukrainian conflict.

The lessons to be learnt are as follows:

Pictured above: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky with Speaker of the House of Commons, Sir Lindsay Hoyle and Speaker of the House of Lords, Lord McFall during Zelensky's visit to London on 9 February 2023.

One year of war in Ukraine has seen the country demonstrate not only its military capacity and resilience, but also its commitment to the rule of law.

As soon as the war began and the nature of the destruction which Russia inflicted on the people of Ukraine became apparent so did discussion of the prosecution of perpetrators of war crimes.

The Prosecutor General of Ukraine began the investigation of war crimes and there has been at least one prosecution of a low-ranking soldier for war crimes. At the international level the International Criminal Court has sent a team to Ukraine and has indicated it is prepared to prosecute war crimes arising out of the conflict. In addition, there has been discussion of establishing a special tribunal to prosecute Russia for the crime of aggression. International assistance has been given to Ukrainian investigators and prosecutors.

However, the reality is that the prosecution on a large scale of the perpetrators of war crimes is unlikely to take place until after the end of the war and upon a significant change in political circumstances.

The fact that Vladimir Putin and senior Russian military officials are in Russia and are likely to remain there is an obstacle to their prosecution. However, that is not to say that Putin and his military leaders will not be prosecuted. It is not impossible that, in the future, circumstances will lead to their prosecution.

This time should be used to devise a strategy as how war crimes committed in Ukraine are investigated and prosecuted effectively and efficiently. There are some useful lessons to be learnt from the investigation and prosecution of war crimes committed during the 1992-95 war in Bosnia Herzegovina.

The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) attracted much attention for its prosecution of high-profile figures such as Radovan Karadzic and Ratko Mladic. But less well known and recognised has been the role of the courts of Bosnia and Herzegovina in the prosecution of war crimes.

The ICTY transferred some of its cases to the Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina (the ‘Court BiH’). Since the ICTY completed its case load, the Court BiH has had sole jurisdiction over the prosecution of war crimes. However, it has transferred some of the less complex cases to local courts across the two entities of Bosnia Herzegovina.

Nearly 30 years after the end of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, many war crimes cases have yet to be prosecuted. No one should expect an early end to the investigation and prosecution of war crimes arising out of the Ukrainian conflict.

The lessons to be learnt are as follows:

Pictured above: Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky with Speaker of the House of Commons, Sir Lindsay Hoyle and Speaker of the House of Lords, Lord McFall during Zelensky's visit to London on 9 February 2023.

On the first anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Mark Guthrie looks at progress on prosecuting Russia’s war crimes and useful lessons to be learnt from the courts of Bosnia and Herzegovina

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

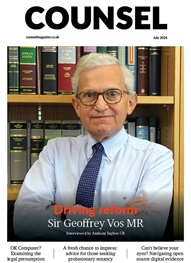

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts