*/

Have you come across the term telematics? Until last year, I hadn’t. It turns out that it’s a combination of the words ‘telecommunications’ (phone lines, cables, etc) and ‘informatics’ (such as computer systems). Vehicle telematics is a way of monitoring vehicles using GPS technology and on-board diagnostics to plot a vehicle’s movements and track events that occur within a vehicle.

Modern vehicles have many computers that function to run the vehicle and perform tasks (such as navigation; making and receiving calls) and in the automotive world, they’re called electronic control units (ECUs). Vehicle systems forensics is the acquisition of data from ECUs and the analysis of that data. It’s very similar to acquiring data from a computer hard drive or mobile phone chip. Every modern vehicle has an ECU and some can be likened to a ‘black box’ in an aircraft. Even if a vehicle has been burnt out, it may still be possible to retrieve data from the ECU (the casing and circuit board may be damaged, but the chip may remain intact).

I recently defended in a murder trial where Wesley Vandiver, an expert in vehicle systems forensics was called to give evidence on behalf of the prosecution. Fortunately, Vandiver’s analysis of the data from a vehicle at the murder scene was largely agreed; I say fortunately because there are very few experts in this field at the moment and his knowledge and level of expertise is internationally recognised.

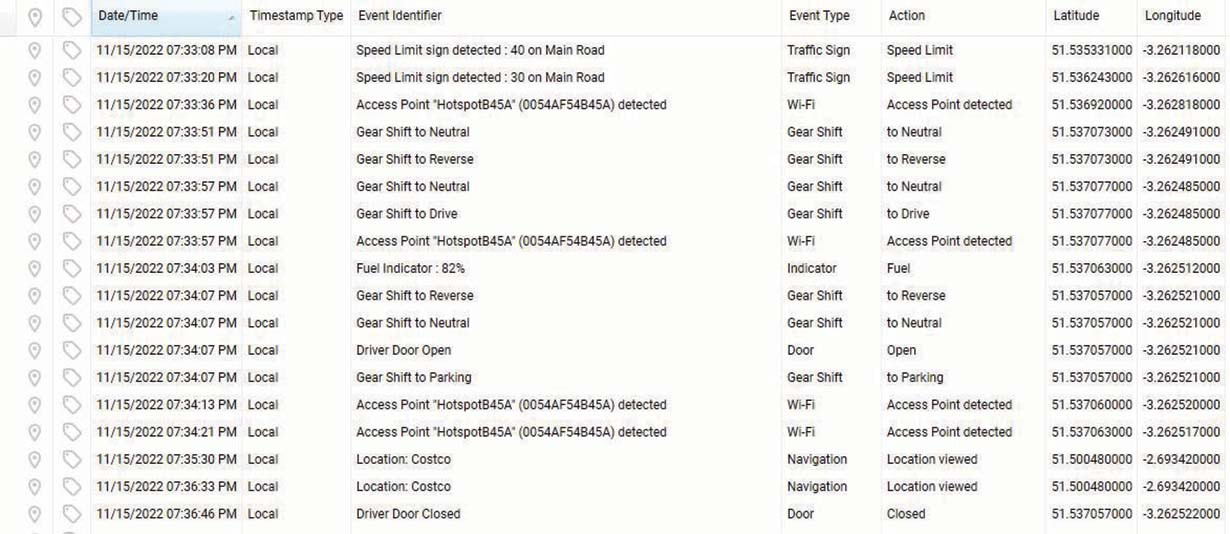

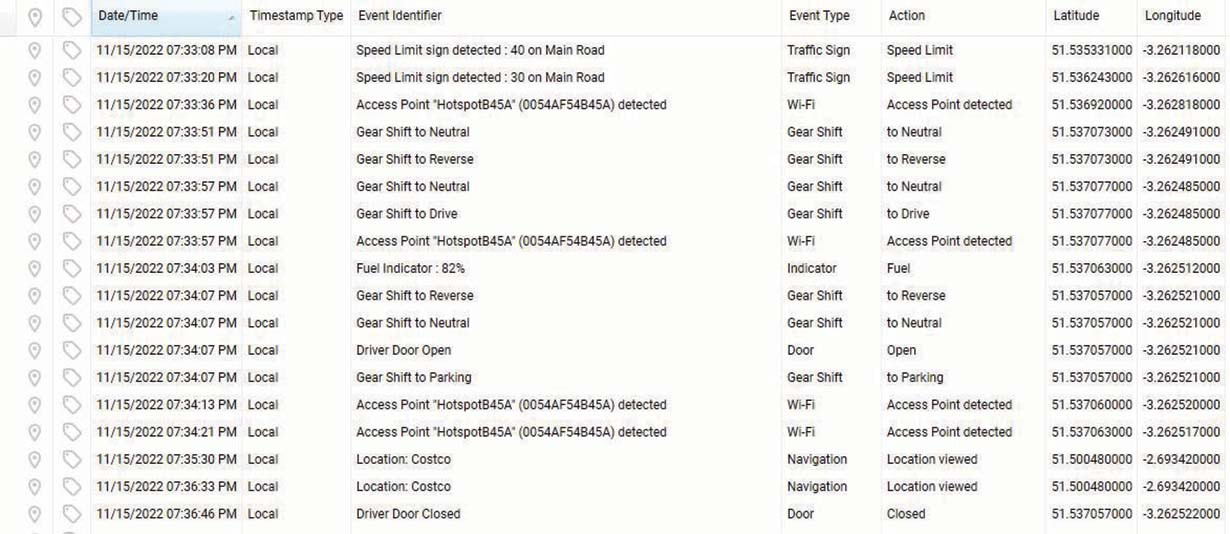

The data acquired from ECUs is in binary form and specialist software is used reacquire it in a logical format. The data in my case was from the vehicle’s infotainment system and it provided information relating to events such as the opening and closing of doors, gear shifts, activation of lights and connections with devices (including methods of connectivity such as USB, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi). GPS data was also acquired identifying the location of the vehicle at any given time which, in turn, was used to derive the vehicle’s speeds between track points.

The primary vehicle network, the Controller Area Network, can only send one message at a time, but messages can be spaced by microseconds. Messages are assigned a priority when sent, so the highest priority messages are received before lower priority messages. For example, a message dealing with stability control (a vehicle safety system) would have priority over the opening of a door.

When analysing the data retrieved, the absence of an event does not necessarily mean that it did not occur whereas positive events can be relied upon as having taken place. An event might not be recorded because it may have occurred prior to the system being awakened (in order for a vehicle to be ‘awake’, it isn’t necessary for the ignition to be switched on, simply that the ECUs within the vehicle are awake). A common example of this is a ‘driver door opened’ event. If the vehicle is asleep (perhaps because it hasn’t been in use overnight) and the driver door is opened, this is the event that will awaken the system, but since it occurred before the system was awake, it will often not be recorded. Data may therefore indicate a ‘driver door closed’ event without a corresponding ‘driver door opened’ event.

When the data acquired from a vehicle is analysed alongside other evidence in a case, such as CCTV, cell-site analysis, and eyewitness testimony, significance can be attributed to the data and it can provide a comprehensive picture of the vehicle’s movements and functions. It is highly accurate and reliable and it can assist the prosecution and/or the defence, depending on the issues in the case.

Take the above example of the ECU recording an event such as the vehicle door opening or closing. Let’s say an eyewitness asserts that a defendant exited the vehicle by the driver’s door during the course of a knife-point robbery. It is said that he exits the vehicle, encourages other defendants to commit the robbery, before quickly retreating to the vehicle and driving off. The defendant denies that he did this; he asserts that he remained in the vehicle throughout and that he didn’t even open the vehicle door. The CCTV footage is too poor to assist and the cell-site evidence doesn’t take matters any further because the defendant accepts being in the vehicle. The telematics data retrieved from the vehicle, providing the vehicle was ‘awake’ at the time, will have recorded a ‘driver door opened’ event and a ‘driver door closed’ event. The absence of this data can be used to robustly challenge the accuracy of the eyewitness testimony, and to positively assert the defendant’s case that he remained in the vehicle.

Another example may be where it is asserted that a defendant reversed an automatic vehicle at a particular point in a road. You read your case papers and consider the telematics data retrieved. You observe the following gear shift events: Drive – Neutral – Reverse – Neutral – Drive. The instructions provided by the defendant note that he resolutely denies reversing the vehicle. Analysis of the data by an expert may be able to assist the defendant’s case in these circumstances. How? Because a gear shift event into Reverse does not necessarily mean that the vehicle did in fact reverse. By analysing all of the available data, it may be possible to confirm that the vehicle was performing the Reverse function for a matter of seconds only. Taken together with GPS data that indicates that the vehicle was not in motion during those seconds, you can now positively challenge the assertion that the vehicle reversed at a particular point.

Although all modern vehicles have multiple ECUs, the data stored varies greatly. The data may go back hours, days, weeks, months, or years – it just depends on the system in the vehicle. Being alert to the fact that data may be available within an ECU will enable you to request disclosure and/or seek guidance from an expert to assist you with obtaining and analysing the relevant material.

Issues that arise in trials often go beyond simply reciting the available data, and analysis is likely to assist you in interpreting the potential significance of recorded events (such as gear shifts and doors opening and closing) and vehicle dynamics (such as acceleration or deceleration). There may be cases where it will be appropriate to consider accident reconstruction as a way of challenging assertions made about how and why a collision occurred.

I’m in no doubt that we will see an increase in reliance on telematics as an instructive and important component part of the evidence in a case where vehicles are involved. Now that you know a bit about telematics and that it may be possible to acquire data from an ECU, when the brief comes your way, you will be better informed as you consider how best to prepare and present your case.

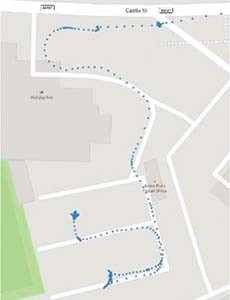

A map plotting track points of the journey.

Have you come across the term telematics? Until last year, I hadn’t. It turns out that it’s a combination of the words ‘telecommunications’ (phone lines, cables, etc) and ‘informatics’ (such as computer systems). Vehicle telematics is a way of monitoring vehicles using GPS technology and on-board diagnostics to plot a vehicle’s movements and track events that occur within a vehicle.

Modern vehicles have many computers that function to run the vehicle and perform tasks (such as navigation; making and receiving calls) and in the automotive world, they’re called electronic control units (ECUs). Vehicle systems forensics is the acquisition of data from ECUs and the analysis of that data. It’s very similar to acquiring data from a computer hard drive or mobile phone chip. Every modern vehicle has an ECU and some can be likened to a ‘black box’ in an aircraft. Even if a vehicle has been burnt out, it may still be possible to retrieve data from the ECU (the casing and circuit board may be damaged, but the chip may remain intact).

I recently defended in a murder trial where Wesley Vandiver, an expert in vehicle systems forensics was called to give evidence on behalf of the prosecution. Fortunately, Vandiver’s analysis of the data from a vehicle at the murder scene was largely agreed; I say fortunately because there are very few experts in this field at the moment and his knowledge and level of expertise is internationally recognised.

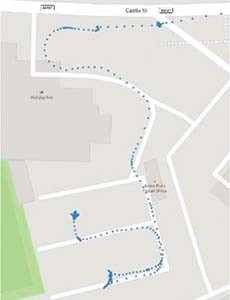

The data acquired from ECUs is in binary form and specialist software is used reacquire it in a logical format. The data in my case was from the vehicle’s infotainment system and it provided information relating to events such as the opening and closing of doors, gear shifts, activation of lights and connections with devices (including methods of connectivity such as USB, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi). GPS data was also acquired identifying the location of the vehicle at any given time which, in turn, was used to derive the vehicle’s speeds between track points.

The primary vehicle network, the Controller Area Network, can only send one message at a time, but messages can be spaced by microseconds. Messages are assigned a priority when sent, so the highest priority messages are received before lower priority messages. For example, a message dealing with stability control (a vehicle safety system) would have priority over the opening of a door.

When analysing the data retrieved, the absence of an event does not necessarily mean that it did not occur whereas positive events can be relied upon as having taken place. An event might not be recorded because it may have occurred prior to the system being awakened (in order for a vehicle to be ‘awake’, it isn’t necessary for the ignition to be switched on, simply that the ECUs within the vehicle are awake). A common example of this is a ‘driver door opened’ event. If the vehicle is asleep (perhaps because it hasn’t been in use overnight) and the driver door is opened, this is the event that will awaken the system, but since it occurred before the system was awake, it will often not be recorded. Data may therefore indicate a ‘driver door closed’ event without a corresponding ‘driver door opened’ event.

When the data acquired from a vehicle is analysed alongside other evidence in a case, such as CCTV, cell-site analysis, and eyewitness testimony, significance can be attributed to the data and it can provide a comprehensive picture of the vehicle’s movements and functions. It is highly accurate and reliable and it can assist the prosecution and/or the defence, depending on the issues in the case.

Take the above example of the ECU recording an event such as the vehicle door opening or closing. Let’s say an eyewitness asserts that a defendant exited the vehicle by the driver’s door during the course of a knife-point robbery. It is said that he exits the vehicle, encourages other defendants to commit the robbery, before quickly retreating to the vehicle and driving off. The defendant denies that he did this; he asserts that he remained in the vehicle throughout and that he didn’t even open the vehicle door. The CCTV footage is too poor to assist and the cell-site evidence doesn’t take matters any further because the defendant accepts being in the vehicle. The telematics data retrieved from the vehicle, providing the vehicle was ‘awake’ at the time, will have recorded a ‘driver door opened’ event and a ‘driver door closed’ event. The absence of this data can be used to robustly challenge the accuracy of the eyewitness testimony, and to positively assert the defendant’s case that he remained in the vehicle.

Another example may be where it is asserted that a defendant reversed an automatic vehicle at a particular point in a road. You read your case papers and consider the telematics data retrieved. You observe the following gear shift events: Drive – Neutral – Reverse – Neutral – Drive. The instructions provided by the defendant note that he resolutely denies reversing the vehicle. Analysis of the data by an expert may be able to assist the defendant’s case in these circumstances. How? Because a gear shift event into Reverse does not necessarily mean that the vehicle did in fact reverse. By analysing all of the available data, it may be possible to confirm that the vehicle was performing the Reverse function for a matter of seconds only. Taken together with GPS data that indicates that the vehicle was not in motion during those seconds, you can now positively challenge the assertion that the vehicle reversed at a particular point.

Although all modern vehicles have multiple ECUs, the data stored varies greatly. The data may go back hours, days, weeks, months, or years – it just depends on the system in the vehicle. Being alert to the fact that data may be available within an ECU will enable you to request disclosure and/or seek guidance from an expert to assist you with obtaining and analysing the relevant material.

Issues that arise in trials often go beyond simply reciting the available data, and analysis is likely to assist you in interpreting the potential significance of recorded events (such as gear shifts and doors opening and closing) and vehicle dynamics (such as acceleration or deceleration). There may be cases where it will be appropriate to consider accident reconstruction as a way of challenging assertions made about how and why a collision occurred.

I’m in no doubt that we will see an increase in reliance on telematics as an instructive and important component part of the evidence in a case where vehicles are involved. Now that you know a bit about telematics and that it may be possible to acquire data from an ECU, when the brief comes your way, you will be better informed as you consider how best to prepare and present your case.

A map plotting track points of the journey.

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts