*/

Certain patterns repeat, but there is always something new to note, finds David Wurtzel, including a second year of large-scale pre-interview sifting and success for the youngsters

‘Silk is awarded for the demonstration of excellence in all the competencies… [It] is for advocacy in the higher courts’. Thus begins the King’s Counsel Selection Panel’s (‘the Panel’s’) Approach to Competencies for the 2023 competition. It is accompanied by the Panel’s Report to the Lord Chancellor on the process of selection and a paper on how feedback is given to those who were unsuccessful. It aims to be thorough and transparent. Apart from the statistics relating to this particular year, much of it is the same as is published for each competition. Applicants in 2023 would have known exactly what is required.

Since the selection process was given to an independent body 18 years ago, certain patterns have repeated themselves. There is, however, always something new to note.

First, this is a process which is totally dominated by self-employed barristers. Every year the Panel report states that the process was designed ‘to enable solicitor advocates to seek appointments with the assurance that they would be assessed fairly alongside barrister applicants.’ It has made little difference. In the eight years before the new system was established, an average 7.8 solicitors applied per year of whom on average only one was appointed. In the 18 years since then, an average of 8.5 solicitors per year have applied of whom an average of 3 have been appointed. This year, as last year, one solicitor was recommended for appointment. Employed barristers do worse: in the last 17 competitions they have averaged five applicants per year, and an average of one successful applicant per year. There is one this year, who is a Crown Prosecution Service advocate.

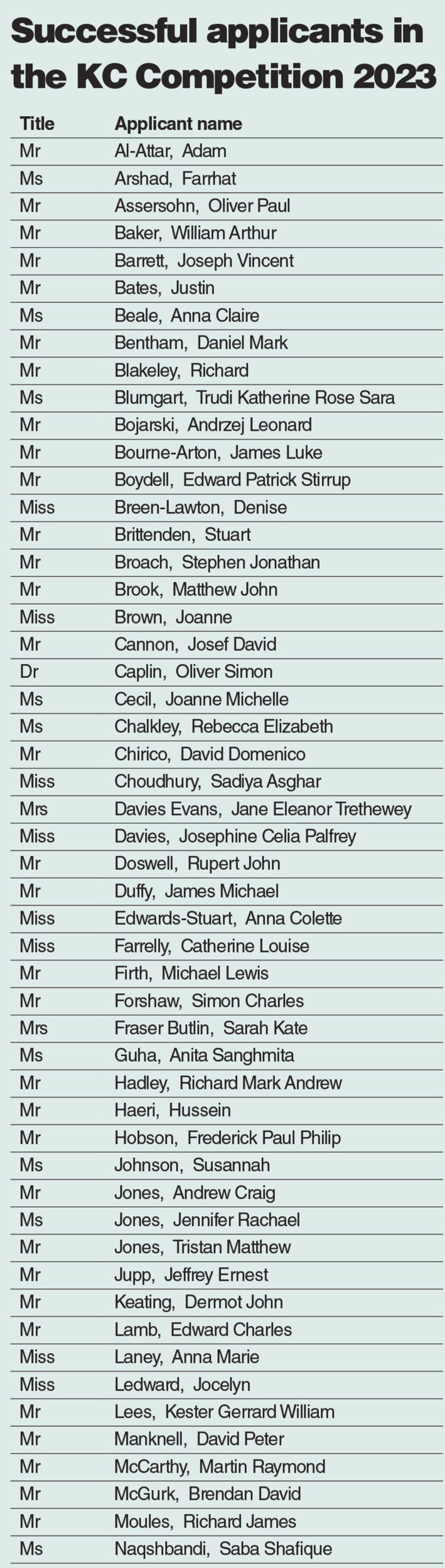

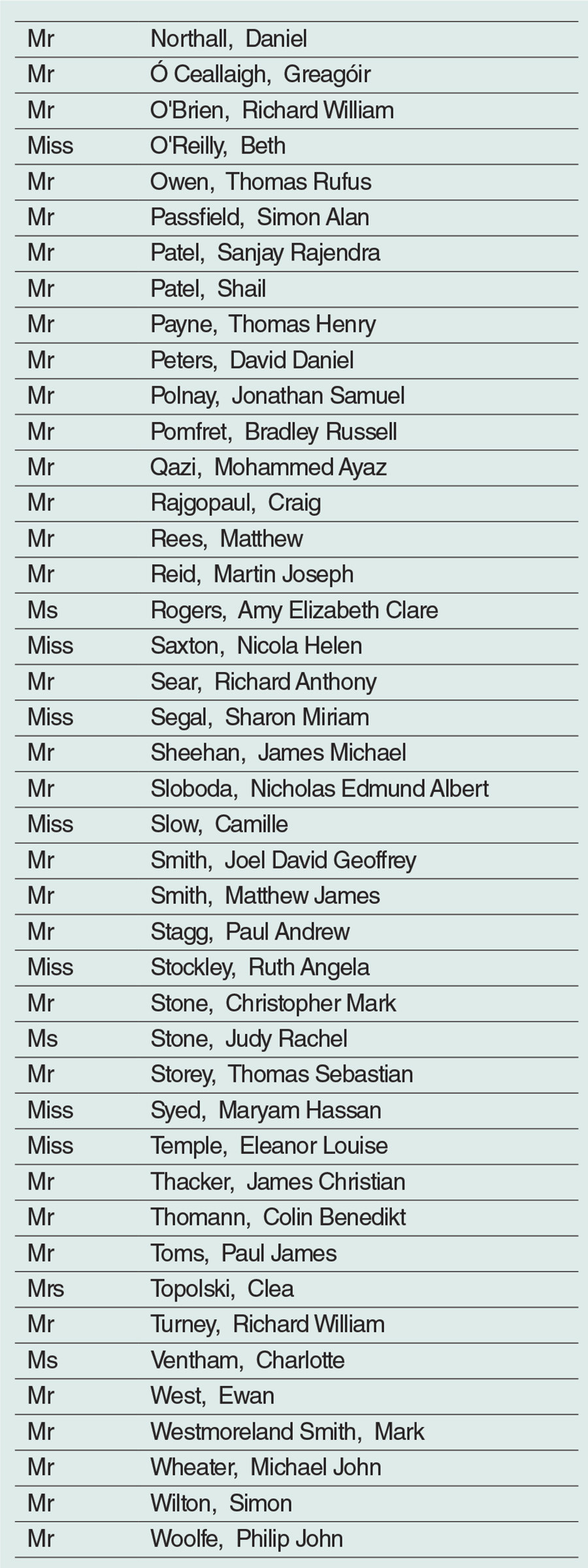

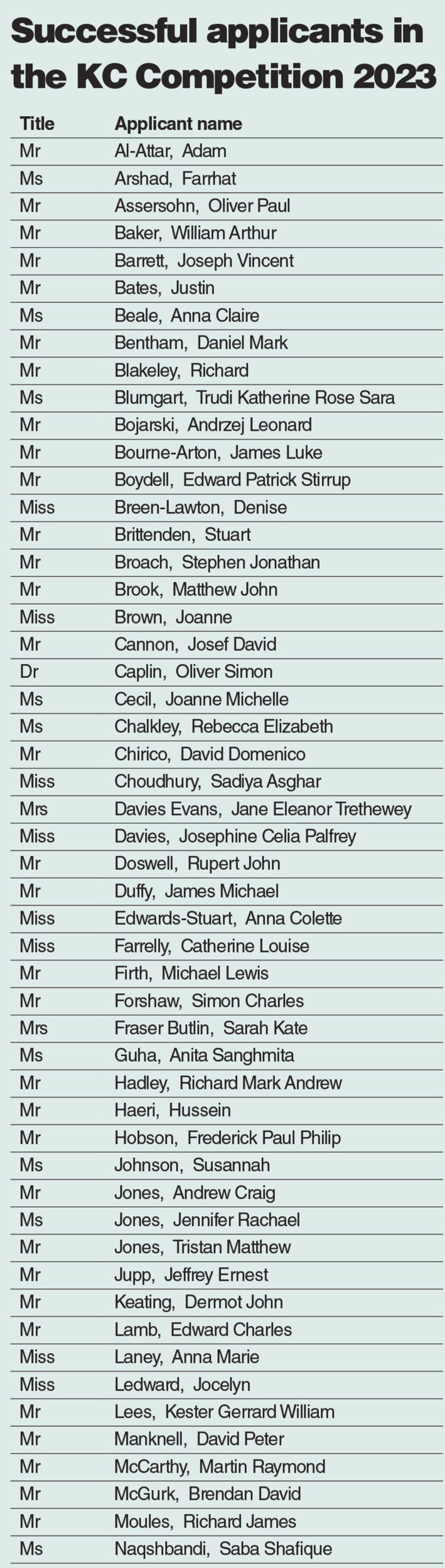

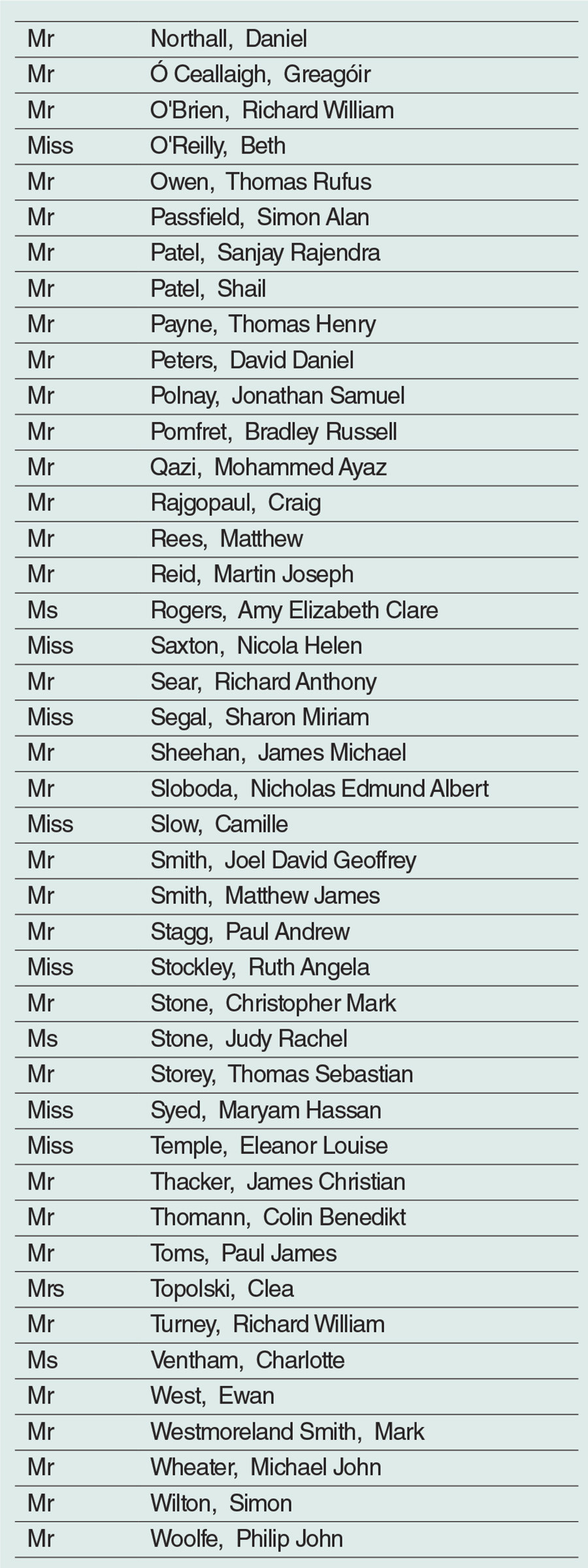

Second, this is a process which is relevant only to a tiny section of the Bar. It looks at the achievements of established practitioners in areas which need leading counsel. They are almost by definition unrepresentative of the Bar at large. There are over 400 sets of chambers with more than one practitioner but fewer than a quarter produce silks. The number of sets is normally in the low 70s. This year there were 67 sets. Of these, 21 produced half the total cohort while the other 46 produced one each. Eight chambers are based outside London: two for civil work, five for crime and one for family. Of the 41 civil sets, 39 have produced silks in at least one of the last three years and often all three. Of the 283 applicants in 2023, 37 were under 40, 73 were 51 or older and 173 were in their 40s.

There is no data on the income of applicants, but the process is not inexpensive. This year it cost £1,975 (up from £1,900) to apply. For those appointed there is a further fee of £3,325 (up from £3,200) quite apart from the cost of buying new professional dress if not hosting a celebration party. However, fees are reduced for those on low earnings. Low earnings are defined as less than £90,000 in fees. Nine applicants took advantage of that, which leaves 274 with higher fee incomes than that. Which in turn puts them at least in the top 2% of earners in this country.

Third, successful applicants come from chambers that already have a substantial number of silks. In most years, every applicant recommended for appointment has been a member of chambers with existing silks. Sometimes there is one ‘first in chambers’. This year there are two out of 95, one specialising in family work and the other in immigration law. In 2023, there are on average 15 silks in each set of chambers of each successful applicant who specialises in family or in criminal work. The average in civil work is 20, if one puts aside the ‘powerhouse’ sets of Brick Court, 39 Essex Street, Blackstone, Essex Court and One Essex Court, each of which have more than 50. Clearly there is no shortage of mentors to hand or colleagues to advise about the process. For those wishing to build up a silk’s practice, it is obvious where that work goes. As usual, there were a few chambers which managed to produce as many as four new silks each: 11 King’s Bench Walk (civil work) and 7 Bedford Row (spread among their civil, family and criminal teams).

Fourth, although each individual has their own story about developing their practice, family and criminal practitioners tend to be called for more than 20 years before applying. Of the 25 with primarily criminal practices, 21 were called in 2001 or earlier. Of the 12 with primarily family practices, 10 were called in 2000 or before. Of the 58 civil practitioners, only 10 were called in the 1990s but 15 were called between 2007 and 2012. In 2023 and once again, it is the youngest who are the most successful and the eldest who are the least. Of the 37 applicants who were aged 40 and under, 22 (59%) were interviewed and 16 (43%) were recommended for appointment (NB the 15 civil practitioners called in 2007 and thereafter). This is substantially above the overall average. Of the 73 applicants who were over the age of 50, only 28 (38%) were interviewed and 18 (25%) were recommended, both well below the overall average.

Fifth, a large proportion of the total applicant cohort is made up of people who have applied at least once in the last three years. This is no bar to subsequent success or guarantee of failure. There were 114 of them, 40% of the total. They did slightly better than the overall average: 40 (35%) were successful. Of those interviewed, 65% were successful, which is also the overall rate. Fifty-three were not invited to interview although 17 of them had been invited the last time they applied.

What is striking this year, and particularly because it repeats last year, is the degree to which the Panel has weeded out applicants before interview. Weeding out is a decision which is taken by the full Panel, not by grading pairs. The approach is that applicants should be interviewed ‘unless it is clear, having considered the assessments from the assessors together with the applicant’s own self-assessment, that they have no reasonable prospects of success’. One notes here that Panel members are not told the date of call or the applicant’s age, ethnicity, disability or whether the applicant had applied previously. Insufficient evidence on the competency of diversity does not exclude an applicant from interview if the interview ‘was merited on the strength of the other competencies’.

There were 283 applications this time, slightly up on 2022’s 279 and 2020’s 281. It is still the highest number since 2007/8. However, since, as in 2022, there were only 95 successful applicants, it is the lowest overall success rate (33.6%) since 2007/8. The filtering process helps to explain this. As in 2022, 48% were not invited for interview; in 2019 it was only 30% who were not. For those who got as far as the interview, there was a 65% success rate. There are other statistics to note. The number of women applicants at 79 was the highest ever – it only exceeded 70 in 2020. Their success rate (38%) was higher than the men’s (31.9%), as it has been in 16 of the last 18 competitions, but only 30 women were recommended for appointment. That is the lowest success rate for women since 2003. Men did slightly better than they did in 2021 and 2022 but otherwise we have to look back to 2007/8 for a similar outcome.

Clearly making the most of your application is crucial. Twelve judicial, 12 practitioner and six client assessors are requested in order to allow the panel to secure the four judicial, three practitioner and two client assessments which the process requires. Forty-eight per cent managed this with only 14 naming fewer than eight judicial assessors.

Of the 95 recommended for appointment, 58 or 61% do civil work only, 10 or 11% do family work only, and 22 or 23% do criminal work. Five do a mixture. This is a fairly traditional distribution. The number of criminal silks soared in the years before 2020 to 38, 40 and 39 before dipping to 25 in 2019, 24 in 2021 and 17 last year.

In respect of civil work, there were 14 women (25%) and 44 men (75%). The cohort includes five Asian/Asian Briton practitioners, one female and four male. If one looks at educational background, which probably loomed large when they were applying for pupillage, there is once more an overwhelming number of Oxbridge graduates. Educational achievement in addition is clearly something the civil practitioners want people to know, since 80% include it in their chambers website entry. Far fewer family and civil practitioners do. Of the successful civil law applicants, at least 36 went to Oxford or Cambridge and 11 to other Russell Group universities. The former includes three DPhils, 13 First Class Degrees (there are four other Firsts among the non-Oxbridge barristers), three Firsts that were the highest or second highest in their year and three starred Firsts.

Of the 10 family practitioners plus the two ‘family and civil’ applicants, five specialise in financial relief: four men and one woman; four of the five went to Oxford or Cambridge. Seven further specialise in children matters (four women, three men). There was one Asian/Asian British barrister and one Black/African/Caribbean barrister, both of whom are women. One man cited his school. In total 58% are men and 42% are women.

Of the criminal practitioners, including the three with mixed practices, 14 are men (56%) and 11 are women (44%). Four are Asian/Asian British, three female and one male. Nine cited their university, four of which were Oxford. Four of the seven non-London sets are represented here.

In terms of ethnicity overall, 48 applicants (17% of the total) declared an ethnicity other than White. They had an overall success rate of 27%, the lowest since 2007/8, with 46% invited to interview.

In addition, KCA published the statistics for the seven years, 2017 to 2023. On average per year, there have been 23 Asian/Asian British applicants. This year was the highest with 29. The average number of successful applicants is 10 (11 this year) or a success rate of 43%. The average number of Black/African/Caribbean applicants is 6.4. The average number of successful applicants is 2.2 (one this year) or a success rate of 34%. On average the number of ‘Other’ (undefined) is eight. The average number of successful applicants is three, or a success rate of 37%. Looking at the three specialisms, 16% had ethnic minority backgrounds among criminal and family practitioners and 8% among civil practitioners.

Not all applicants declared a sexuality. Of those who did, 13 identified as gay men and one as a gay woman. Of the 14, 10 were interviewed and seven were recommended for appointment, a typical success rate for LGBT+ applicants. Of the 17 applicants who declared a disability, nine were interviewed and eight were recommended for appointment. These figures are not matched against specialisms or ethnicity.

Each unsuccessful applicant receives individual feedback. One hopes that some day they will allow access to this to a researcher who will then be in a position to explore why applicants have been unsuccessful. It might assist future applicants. In the meantime, the answer to ‘why were they unsuccessful?’ is speculation.

‘Silk is awarded for the demonstration of excellence in all the competencies… [It] is for advocacy in the higher courts’. Thus begins the King’s Counsel Selection Panel’s (‘the Panel’s’) Approach to Competencies for the 2023 competition. It is accompanied by the Panel’s Report to the Lord Chancellor on the process of selection and a paper on how feedback is given to those who were unsuccessful. It aims to be thorough and transparent. Apart from the statistics relating to this particular year, much of it is the same as is published for each competition. Applicants in 2023 would have known exactly what is required.

Since the selection process was given to an independent body 18 years ago, certain patterns have repeated themselves. There is, however, always something new to note.

First, this is a process which is totally dominated by self-employed barristers. Every year the Panel report states that the process was designed ‘to enable solicitor advocates to seek appointments with the assurance that they would be assessed fairly alongside barrister applicants.’ It has made little difference. In the eight years before the new system was established, an average 7.8 solicitors applied per year of whom on average only one was appointed. In the 18 years since then, an average of 8.5 solicitors per year have applied of whom an average of 3 have been appointed. This year, as last year, one solicitor was recommended for appointment. Employed barristers do worse: in the last 17 competitions they have averaged five applicants per year, and an average of one successful applicant per year. There is one this year, who is a Crown Prosecution Service advocate.

Second, this is a process which is relevant only to a tiny section of the Bar. It looks at the achievements of established practitioners in areas which need leading counsel. They are almost by definition unrepresentative of the Bar at large. There are over 400 sets of chambers with more than one practitioner but fewer than a quarter produce silks. The number of sets is normally in the low 70s. This year there were 67 sets. Of these, 21 produced half the total cohort while the other 46 produced one each. Eight chambers are based outside London: two for civil work, five for crime and one for family. Of the 41 civil sets, 39 have produced silks in at least one of the last three years and often all three. Of the 283 applicants in 2023, 37 were under 40, 73 were 51 or older and 173 were in their 40s.

There is no data on the income of applicants, but the process is not inexpensive. This year it cost £1,975 (up from £1,900) to apply. For those appointed there is a further fee of £3,325 (up from £3,200) quite apart from the cost of buying new professional dress if not hosting a celebration party. However, fees are reduced for those on low earnings. Low earnings are defined as less than £90,000 in fees. Nine applicants took advantage of that, which leaves 274 with higher fee incomes than that. Which in turn puts them at least in the top 2% of earners in this country.

Third, successful applicants come from chambers that already have a substantial number of silks. In most years, every applicant recommended for appointment has been a member of chambers with existing silks. Sometimes there is one ‘first in chambers’. This year there are two out of 95, one specialising in family work and the other in immigration law. In 2023, there are on average 15 silks in each set of chambers of each successful applicant who specialises in family or in criminal work. The average in civil work is 20, if one puts aside the ‘powerhouse’ sets of Brick Court, 39 Essex Street, Blackstone, Essex Court and One Essex Court, each of which have more than 50. Clearly there is no shortage of mentors to hand or colleagues to advise about the process. For those wishing to build up a silk’s practice, it is obvious where that work goes. As usual, there were a few chambers which managed to produce as many as four new silks each: 11 King’s Bench Walk (civil work) and 7 Bedford Row (spread among their civil, family and criminal teams).

Fourth, although each individual has their own story about developing their practice, family and criminal practitioners tend to be called for more than 20 years before applying. Of the 25 with primarily criminal practices, 21 were called in 2001 or earlier. Of the 12 with primarily family practices, 10 were called in 2000 or before. Of the 58 civil practitioners, only 10 were called in the 1990s but 15 were called between 2007 and 2012. In 2023 and once again, it is the youngest who are the most successful and the eldest who are the least. Of the 37 applicants who were aged 40 and under, 22 (59%) were interviewed and 16 (43%) were recommended for appointment (NB the 15 civil practitioners called in 2007 and thereafter). This is substantially above the overall average. Of the 73 applicants who were over the age of 50, only 28 (38%) were interviewed and 18 (25%) were recommended, both well below the overall average.

Fifth, a large proportion of the total applicant cohort is made up of people who have applied at least once in the last three years. This is no bar to subsequent success or guarantee of failure. There were 114 of them, 40% of the total. They did slightly better than the overall average: 40 (35%) were successful. Of those interviewed, 65% were successful, which is also the overall rate. Fifty-three were not invited to interview although 17 of them had been invited the last time they applied.

What is striking this year, and particularly because it repeats last year, is the degree to which the Panel has weeded out applicants before interview. Weeding out is a decision which is taken by the full Panel, not by grading pairs. The approach is that applicants should be interviewed ‘unless it is clear, having considered the assessments from the assessors together with the applicant’s own self-assessment, that they have no reasonable prospects of success’. One notes here that Panel members are not told the date of call or the applicant’s age, ethnicity, disability or whether the applicant had applied previously. Insufficient evidence on the competency of diversity does not exclude an applicant from interview if the interview ‘was merited on the strength of the other competencies’.

There were 283 applications this time, slightly up on 2022’s 279 and 2020’s 281. It is still the highest number since 2007/8. However, since, as in 2022, there were only 95 successful applicants, it is the lowest overall success rate (33.6%) since 2007/8. The filtering process helps to explain this. As in 2022, 48% were not invited for interview; in 2019 it was only 30% who were not. For those who got as far as the interview, there was a 65% success rate. There are other statistics to note. The number of women applicants at 79 was the highest ever – it only exceeded 70 in 2020. Their success rate (38%) was higher than the men’s (31.9%), as it has been in 16 of the last 18 competitions, but only 30 women were recommended for appointment. That is the lowest success rate for women since 2003. Men did slightly better than they did in 2021 and 2022 but otherwise we have to look back to 2007/8 for a similar outcome.

Clearly making the most of your application is crucial. Twelve judicial, 12 practitioner and six client assessors are requested in order to allow the panel to secure the four judicial, three practitioner and two client assessments which the process requires. Forty-eight per cent managed this with only 14 naming fewer than eight judicial assessors.

Of the 95 recommended for appointment, 58 or 61% do civil work only, 10 or 11% do family work only, and 22 or 23% do criminal work. Five do a mixture. This is a fairly traditional distribution. The number of criminal silks soared in the years before 2020 to 38, 40 and 39 before dipping to 25 in 2019, 24 in 2021 and 17 last year.

In respect of civil work, there were 14 women (25%) and 44 men (75%). The cohort includes five Asian/Asian Briton practitioners, one female and four male. If one looks at educational background, which probably loomed large when they were applying for pupillage, there is once more an overwhelming number of Oxbridge graduates. Educational achievement in addition is clearly something the civil practitioners want people to know, since 80% include it in their chambers website entry. Far fewer family and civil practitioners do. Of the successful civil law applicants, at least 36 went to Oxford or Cambridge and 11 to other Russell Group universities. The former includes three DPhils, 13 First Class Degrees (there are four other Firsts among the non-Oxbridge barristers), three Firsts that were the highest or second highest in their year and three starred Firsts.

Of the 10 family practitioners plus the two ‘family and civil’ applicants, five specialise in financial relief: four men and one woman; four of the five went to Oxford or Cambridge. Seven further specialise in children matters (four women, three men). There was one Asian/Asian British barrister and one Black/African/Caribbean barrister, both of whom are women. One man cited his school. In total 58% are men and 42% are women.

Of the criminal practitioners, including the three with mixed practices, 14 are men (56%) and 11 are women (44%). Four are Asian/Asian British, three female and one male. Nine cited their university, four of which were Oxford. Four of the seven non-London sets are represented here.

In terms of ethnicity overall, 48 applicants (17% of the total) declared an ethnicity other than White. They had an overall success rate of 27%, the lowest since 2007/8, with 46% invited to interview.

In addition, KCA published the statistics for the seven years, 2017 to 2023. On average per year, there have been 23 Asian/Asian British applicants. This year was the highest with 29. The average number of successful applicants is 10 (11 this year) or a success rate of 43%. The average number of Black/African/Caribbean applicants is 6.4. The average number of successful applicants is 2.2 (one this year) or a success rate of 34%. On average the number of ‘Other’ (undefined) is eight. The average number of successful applicants is three, or a success rate of 37%. Looking at the three specialisms, 16% had ethnic minority backgrounds among criminal and family practitioners and 8% among civil practitioners.

Not all applicants declared a sexuality. Of those who did, 13 identified as gay men and one as a gay woman. Of the 14, 10 were interviewed and seven were recommended for appointment, a typical success rate for LGBT+ applicants. Of the 17 applicants who declared a disability, nine were interviewed and eight were recommended for appointment. These figures are not matched against specialisms or ethnicity.

Each unsuccessful applicant receives individual feedback. One hopes that some day they will allow access to this to a researcher who will then be in a position to explore why applicants have been unsuccessful. It might assist future applicants. In the meantime, the answer to ‘why were they unsuccessful?’ is speculation.

Certain patterns repeat, but there is always something new to note, finds David Wurtzel, including a second year of large-scale pre-interview sifting and success for the youngsters

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts