*/

Brexit shows that our late 19th century uncodified constitution should be replaced by a 21st century written one, argues Austen Morgan

The moment of Brexit, from 2016 to 2020, is unprecedented. The metropolitan elite remains critical of Theresa May, and especially Boris Johnson, following the referendum, for legally ending UK membership of the EU. Others (including myself) criticise additionally: the negative role of Parliament; and especially the Supreme Court decision in the case brought by Joanna Cherry KC MP and Gina Miller on prorogation.

In Pretence: why the United Kingdom needs a written constitution (Black Spring Press Group: 2023), a book written during the pandemic, I argue that Brexit shows that the late 19th century uncodified constitution should be replaced by a 21st-century written constitution (like most states in the world), for a number of reasons.

One, the EU taught us how to run on fundamental law for over four decades. That is opportunity. Two, the project of a constitutional UK Bill of Rights (which paused with Dominic Raab). That is (or rather, would have been) desirability. And three, the possibility of federalisation to maintain the territorial integrity of the state (keeping Scotland). That is imperative.

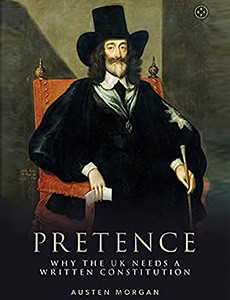

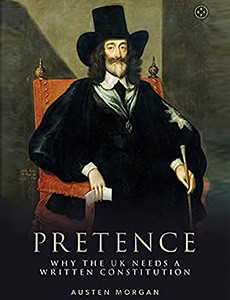

The jacket of the book – Edward Bower’s 1649 portrait of Charles I commissioned by a parliamentary family (chosen before we had a Charles III) – points up the pretence of continuing monarchical authority over the people, when it is political parties in Parliament which make and unmake ministers and shadow ministers; our new King might have sought a revised title of defender of faith from MPs and peers, though he is more likely (judging by his performance so far) to step into a constitutional crisis unwittingly.

I trace my big idea from a Birmingham legal academic, Owen Hood Phillips, and his Reform of the Constitution (Chatto & Windus: 1970). Lord Hailsham’s derivative overblown ‘elective dictatorship’ critique of 1976 resonated popularly to no political effect. In 2014, Lord Neuberger, when President of the Supreme Court, considered codification in an important speech in Bangor, Wales. But it is Sir Vernon Bogdanor, now of King’s College, London, and sprightly as ever, who has been consistently arguing for a written constitution since the millennium began.

I know that David Cameron considered the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta in 2015 as appropriate for a UK Bill of Rights. And I learned recently that Gordon Brown, when Prime Minister, in 2007-10, and still overshadowed by Tony Blair, saw it as a suitable occasion for a UK written constitution, if he had remained in office.

Our constitutional law – whatever of a thousand years of historical continuity since the Norman invasion – dates (I conclude) from A V Dicey’s Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (Macmillan and Co: 1885). Dicey’s triptych – parliamentary sovereignty, rule of law and conventions – has been canonical. I beg to dissent. Parliamentary sovereignty is a confusing way of affirming that Parliament is the principal source of domestic law in our dualist state (with the role of the courts downgraded – according to Dicey – to subordinate law).

Dicey quoted another Oxford legal academic, James Bryce, born in Belfast of Ulster Scots background, as having contrasted in 1884 the UK’s flexible constitution favourably with rigid written constitutions. Dicey never updated his quoting of Bryce, even after the latter’s much-better two-volume book, The American Commonwealth (Macmillan and Co: 1888), where Bryce affirmed the 1789 US federal constitution as very far from rigid. So much for flexibility versus rigidity!

It was the 2019 Conservative manifesto which first proposed unusually a Commission on the Constitution (and I invite the political parties competitively to think about this in 2024). The Johnson government was blown off course by the pandemic from March 2020, and Sir Anthony Seldon and Raymond Newell have shown recently the inconsistencies of prime ministerial rule until July 2022 in Johnson at 10: the inside story (Atlantic Books: 2023).

For myself, I argue that a sans-culottes government occupied Number 10 in July 2019, only to be legitmised in the December 2019 general election, before falling political victim to Patterson, Partygate and Pincher and the fatal revenge (on the third scandal) of the Whitehall mandarinate.

I do not – contrary to anticipations – propose any choice constitutional reforms, such as what to do with the House of Lords. Pretence advocates a written constitution tout court. A Commission on the Constitution could advise on alternatives, however prosaic or visionary; that is the time for such advice.

A written constitution is a major project, requiring the correct historical circumstances, at the beginning, middle and end. It would also have to be popular: perhaps with a constitutional document drafted by the law commissions; with parliamentary committees in the lords and commons advising; then parliamentary legislation; with the people of English, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland approving – or not – their buy-ins as well as the whole package in related referendums.

I have resisted all temptations to draft any provision, including the principle of popular sovereignty in a monarchy (Spain did it in 1978), with an exception: the book ends with a draft preamble, purporting to summarise 1,000 years of English/British/UK historical exceptionalism.

There are three precedents for a codified constitution. First, a text from the left-leaning Institute for Public Policy Research in 1991: ‘This Constitution has been drafted [began the preface] in the conviction that an example would advance the public argument more effectively than further general discussion of the problems which it raises and attempts to resolve.’ I agree wholeheartedly.

Second, a text from Vernon Bogdanor’s students at Oxford in 2006. Their project was to codify the existing constitution. Arguably, this raises questions about why we do things this way and not that way.

And third, the work of the political and constitutional reform committee in the house of commons, chaired by Graham Allen MP in 2014-15, with advice from Prof Robert Blackburn and Dr Andrew Blick. A written constitution was one of three options, which missed the magna carta boat because of the Cameron/Clegg coalition being insufficiently attracted towards the end of that government.

In the bitter 2019 days of Remain v Leave, the Constitution Society published Good Chaps No More?: safeguarding the constitution in stressful times, by Andrew Blick and Peter Hennessy. ‘It may be a source of regret for some,’ they concluded, ‘but certain elements of the venerable perhaps romantic “good chap” state of mind need now to be codified in cold hard prose.’

Historians may disagree about who Blick and Hennessy’s bad chaps were, but is there not a consensus here to get beyond Brexit and the risk of repetition of future constitutional crises? I offer the hand of friendship to these fellow constitutionalists, as well as to other like-minded lawyers, politicians and political activists! Let us begin… or rather resume.

The author's book, Pretence: why the United Kingdom needs a written constitution, was published by the Black Spring Press Group on 30 May 2023.

The moment of Brexit, from 2016 to 2020, is unprecedented. The metropolitan elite remains critical of Theresa May, and especially Boris Johnson, following the referendum, for legally ending UK membership of the EU. Others (including myself) criticise additionally: the negative role of Parliament; and especially the Supreme Court decision in the case brought by Joanna Cherry KC MP and Gina Miller on prorogation.

In Pretence: why the United Kingdom needs a written constitution (Black Spring Press Group: 2023), a book written during the pandemic, I argue that Brexit shows that the late 19th century uncodified constitution should be replaced by a 21st-century written constitution (like most states in the world), for a number of reasons.

One, the EU taught us how to run on fundamental law for over four decades. That is opportunity. Two, the project of a constitutional UK Bill of Rights (which paused with Dominic Raab). That is (or rather, would have been) desirability. And three, the possibility of federalisation to maintain the territorial integrity of the state (keeping Scotland). That is imperative.

The jacket of the book – Edward Bower’s 1649 portrait of Charles I commissioned by a parliamentary family (chosen before we had a Charles III) – points up the pretence of continuing monarchical authority over the people, when it is political parties in Parliament which make and unmake ministers and shadow ministers; our new King might have sought a revised title of defender of faith from MPs and peers, though he is more likely (judging by his performance so far) to step into a constitutional crisis unwittingly.

I trace my big idea from a Birmingham legal academic, Owen Hood Phillips, and his Reform of the Constitution (Chatto & Windus: 1970). Lord Hailsham’s derivative overblown ‘elective dictatorship’ critique of 1976 resonated popularly to no political effect. In 2014, Lord Neuberger, when President of the Supreme Court, considered codification in an important speech in Bangor, Wales. But it is Sir Vernon Bogdanor, now of King’s College, London, and sprightly as ever, who has been consistently arguing for a written constitution since the millennium began.

I know that David Cameron considered the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta in 2015 as appropriate for a UK Bill of Rights. And I learned recently that Gordon Brown, when Prime Minister, in 2007-10, and still overshadowed by Tony Blair, saw it as a suitable occasion for a UK written constitution, if he had remained in office.

Our constitutional law – whatever of a thousand years of historical continuity since the Norman invasion – dates (I conclude) from A V Dicey’s Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (Macmillan and Co: 1885). Dicey’s triptych – parliamentary sovereignty, rule of law and conventions – has been canonical. I beg to dissent. Parliamentary sovereignty is a confusing way of affirming that Parliament is the principal source of domestic law in our dualist state (with the role of the courts downgraded – according to Dicey – to subordinate law).

Dicey quoted another Oxford legal academic, James Bryce, born in Belfast of Ulster Scots background, as having contrasted in 1884 the UK’s flexible constitution favourably with rigid written constitutions. Dicey never updated his quoting of Bryce, even after the latter’s much-better two-volume book, The American Commonwealth (Macmillan and Co: 1888), where Bryce affirmed the 1789 US federal constitution as very far from rigid. So much for flexibility versus rigidity!

It was the 2019 Conservative manifesto which first proposed unusually a Commission on the Constitution (and I invite the political parties competitively to think about this in 2024). The Johnson government was blown off course by the pandemic from March 2020, and Sir Anthony Seldon and Raymond Newell have shown recently the inconsistencies of prime ministerial rule until July 2022 in Johnson at 10: the inside story (Atlantic Books: 2023).

For myself, I argue that a sans-culottes government occupied Number 10 in July 2019, only to be legitmised in the December 2019 general election, before falling political victim to Patterson, Partygate and Pincher and the fatal revenge (on the third scandal) of the Whitehall mandarinate.

I do not – contrary to anticipations – propose any choice constitutional reforms, such as what to do with the House of Lords. Pretence advocates a written constitution tout court. A Commission on the Constitution could advise on alternatives, however prosaic or visionary; that is the time for such advice.

A written constitution is a major project, requiring the correct historical circumstances, at the beginning, middle and end. It would also have to be popular: perhaps with a constitutional document drafted by the law commissions; with parliamentary committees in the lords and commons advising; then parliamentary legislation; with the people of English, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland approving – or not – their buy-ins as well as the whole package in related referendums.

I have resisted all temptations to draft any provision, including the principle of popular sovereignty in a monarchy (Spain did it in 1978), with an exception: the book ends with a draft preamble, purporting to summarise 1,000 years of English/British/UK historical exceptionalism.

There are three precedents for a codified constitution. First, a text from the left-leaning Institute for Public Policy Research in 1991: ‘This Constitution has been drafted [began the preface] in the conviction that an example would advance the public argument more effectively than further general discussion of the problems which it raises and attempts to resolve.’ I agree wholeheartedly.

Second, a text from Vernon Bogdanor’s students at Oxford in 2006. Their project was to codify the existing constitution. Arguably, this raises questions about why we do things this way and not that way.

And third, the work of the political and constitutional reform committee in the house of commons, chaired by Graham Allen MP in 2014-15, with advice from Prof Robert Blackburn and Dr Andrew Blick. A written constitution was one of three options, which missed the magna carta boat because of the Cameron/Clegg coalition being insufficiently attracted towards the end of that government.

In the bitter 2019 days of Remain v Leave, the Constitution Society published Good Chaps No More?: safeguarding the constitution in stressful times, by Andrew Blick and Peter Hennessy. ‘It may be a source of regret for some,’ they concluded, ‘but certain elements of the venerable perhaps romantic “good chap” state of mind need now to be codified in cold hard prose.’

Historians may disagree about who Blick and Hennessy’s bad chaps were, but is there not a consensus here to get beyond Brexit and the risk of repetition of future constitutional crises? I offer the hand of friendship to these fellow constitutionalists, as well as to other like-minded lawyers, politicians and political activists! Let us begin… or rather resume.

The author's book, Pretence: why the United Kingdom needs a written constitution, was published by the Black Spring Press Group on 30 May 2023.

Brexit shows that our late 19th century uncodified constitution should be replaced by a 21st century written one, argues Austen Morgan

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts