*/

‘I have always done what I found really interesting and stimulating. I realise I have been incredibly lucky to have been able to do that. I have been a barrister, sitcom writer, written film scripts and plays. I have also been a BBC broadcaster and journalist and presented a Panorama,’ says Clive Coleman.

The UK is very much open but we are having this conversation over Zoom in September. Perhaps unbecoming of a barrister, I quickly inform Clive that my preparation for this interview began on Wikipedia. There I was blown away by what he later describes as the ‘ridiculous variety’ of his career. He gives the kind of warning that would be expected from a former journalist and teacher: ‘You can’t believe everything you read on [Wikipedia]’ but he assures me that relying on his page would not put me in contempt with Counsel’s readers.

Clive studied English literature at the University of York before taking a law conversion course. Called to the Bar in 1986, he first practised from the Chambers of Robin Stewart QC where, he says, ‘like almost every young barrister in a general common law set, you did anything that came through the door’. This meant Crown Prosecution Service lists, a few jury trials, criminal work that spun off from the civil side and knockabout work in the Magistrates’ Court. He lights up when talking about those early experiences as a courtroom advocate – it is clear this is what he loved about being a barrister.

When reflecting on his first choice of career, I learn that this love was developed at a much earlier stage. He tells me about his father who ‘was a sort of a lawyer; a patent attorney who had come from a very humble background in Leeds. He had always wanted to be a barrister, but never had the money.’ Eventually, his father got a state scholarship and did an engineering degree at Oxford University. Clive describes his father’s office on Fleet Street and recalls walks with him around the Inns of Court. He jokes: ‘Our family are just words… it is all we can do. We could not add up a row of figures to save our lives, but we are very wordy. I grew up in an atmosphere where language and how you expressed yourself and structuring an argument was always quite important.’ As somebody who also enjoys being on stage, I am glad he admits: ‘There was also certainly an aspect of performing that I liked about it.’

However, in 1990 Clive left full-time practice at the Bar to teach on what was then the Bar Vocational Course (BVC). Alongside this he was able to develop a creative writing career, which comprises the largest part of his Wikipedia page. Sticking close to his ‘practice area’, the first big show Clive wrote was Chambers, a comedy series set around barristers.

When I ask about the impetus for writing the show, he explains: ‘There is something grand and theatrical about a courtroom and being a barrister. There is almost a feeling that barristers are not as desperate and ambitious as everyone else [though] of course they are. With the tremendous tradition, grandeur and costume on the one hand, and the fact that barristers were just like everyone else and as capable of taking shortcuts, and those kinds of things, I thought there was a good comic interface.’ Clearly, others agreed. The show launched on BBC Radio 4 in 1996, ran for three series, before transferring to BBC One for two hit television series.

I push Clive on whether his creativity is restricted to writing about the law. He says that every writer should write what he knows. However, there is more to it and he returns to the point about language: ‘Courtrooms are fantastic settings for the very intricate use, and sometimes hilarious misuse, of language. I just find that type of writing is something that I really, really enjoy,’ he says.

Reflecting on memories from early practice, he describes ‘moments where barristers don’t know what on earth they are going to say next, [but] they still sound very, very fluent. So, they will say things like, “And... I have two points to make and those are these, if I may, and I will take the first of those two points now…” They haven’t actually said anything, but it sounds fantastic. I love all the barristers’ tricks of the trade.’ I pause to take some notes for my next hearing in front of a district judge.

Since Chambers, Clive has amassed a range of writing credits on popular comedy shows. However, I cannot waste the opportunity to ask him about his experience writing for one of my favourite legal dramas: The Bill. I have fond memories of sitting next to my dad watching it as a child. However, Clive explains that writing on it ‘was really hard because you were part of a massive jigsaw puzzle, and the pieces were changing fairly regularly. I admired the show, but it was also pure drama and I think I was missing doing gags. Comedy drama is about as much drama as I can handle!’ I wonder whether we both shed a tear when Sun Hill closed its doors.

Nonetheless, as an avid comedy lover and very amateur comedy writer, I understand what keeps pulling him back. He tells me about one of his early opportunities with the BBC, writing comedy news radio sketches. ‘The story was about Sarah Ferguson having her toe sucked by her Texan financial adviser, a guy called John Bryan. Someone in the room said, “Any sketch ideas on this?” “Not tonight, darling, I’ve got a verruca,” was the first gag and then people just [started] topping each other out.’

As he tells the story, he describes that feeling of elation of being in a room with minds working in a similar way. ‘I cannot paint a picture. I’m not musical. But a painter or musician would feel at home with other artists in this way. I really enjoy it. I think this is using my mind in the way that it was meant to be used. So I will do a bit more of it.’

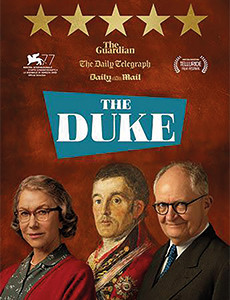

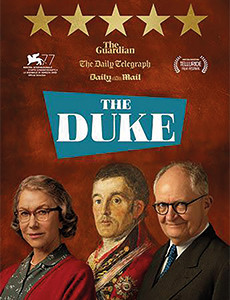

We switch to his current creative project – The Duke – a comedy film he co-wrote with long-term writing partner Richard Bean. It tells the story of Kempton Bunton, a Newcastle cab driver prosecuted for the 1961 theft of Francisco Goya’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington from the National Gallery in London. He describes it as ‘a fantastic true story from the 1960s that everyone had forgotten about and culminated in a fantastic trial at the Old Bailey’. For something like this to be brought to life, ‘you need genius performers for it to absolutely catch fire and obviously a great director’. I can hear the excitement as he reels off the star-studded cast – Jim Broadbent, Helen Mirren, Matthew Goode, Sian Clifford, Fionn Whitehead and Anna Maxwell Martin – directed by the ‘brilliant’ Roger Michell. The film premiered at Venice in June 2020 to positive acclaim. The pandemic means the rest of us will have to wait until February 2022 for its release. (Very sadly, after my interview with Clive, I learn that Roger Michell, the director of The Duke, died suddenly. Roger will not now see the film released and Clive tells me how devastated all those involved in the film were.)

As we continue our discussion, I am interested in exploring Clive’s journalism career. From 2004-2010, he presented the BBC’s flagship legal analysis programme: Law in Action on Radio 4, a role for which he had no formal training. I ask him what is more nerve-wracking: standing up in the Court of Appeal in front of three brilliant judges, having your arguments dismantled limb by limb, phrase by phrase, or to be a live broadcaster. Without hesitation he says, ‘a live broadcaster… because if you get it wrong in court, maybe 20 people would get to know about it. But if you do it in front of four million people, it is utterly terrifying, humiliating and the stakes are just so much higher. No contest.’

He is quick to say, however, that ‘my lawyer’s training helped me avoid some of the very obvious elephant traps.’ This is a point he makes a number of times – ‘the discipline, analysing things critically, being able to go to the absolute essence of a piece of information to winnow out the stuff you don’t need, to focus and make the most of the really important stuff. All that is fantastically good training. That’s the thread that has really gone through pretty much everything I’ve done.’

In 2010, he took on a new role in journalism when he became the BBC’s Legal Correspondent, a position the broadcaster had previously left unfilled. During this time, he covered some of the biggest domestic and international legal stories including the London Riots, the courts backlog and release of the London Bridge terrorist, Usman Khan. He explains: ‘My brief was The Law, not just landlord and tenant or defamation. It was divorce, privacy, property, international law, human rights law, judicial review... it was everything!’

I laugh when he describes how, as a legal reporter, his experience as a BVC teacher meant he would be sitting in court and realise, ‘I had taught the QC and then I thought, hang on, I’m sure I taught the judge. There are now some High Court judges that I actually taught.’ There is something poetic about his diversity of careers meeting in the courtroom.

The story that has had the greatest impact on him, no doubt, is the prorogation case. He explains: ‘It was a massive case. It was a fantastic insight for people into how the constitution of the country actually works. This clash, if you like, between the very powerful executive on the one hand, and the independent judiciary on the other who, through the mechanism of judicial review, have the power to stop Ministers in their tracks if what they are proposing to do or have done is unlawful.’

He goes on: ‘I think people didn’t quite get that that could happen and that nobody is above the law.’ It was this story for which he won the Bar Council Legal Broadcasting Award in 2019 for the second time. We take a brief moment to fawn over Lord Pannick QC.

We are nearing the end of the interview and we discuss his most recent work, which is absent from his Wikipedia page: litigation PR. He explains that ‘there is a case that can be won and lost in the courtroom and there is a case that can be won and lost outside the courtroom as well,’ citing the example of Harry and Meghan and their litigation with the Daily Mail. Adding another string to his legal bow, Clive now works with Maltin PR assisting law firms in this area.

On my count, Clive has had at least five careers. I would be doing a disservice if I did not end our interview by asking him which was his favourite.

‘If I’m honest, I think the thing that I ultimately, probably, feel I get most satisfaction from is constructing a piece of fiction; whether it’s a half-hour sitcom or a one-and-a-half-hour film script that works.’ Like any good barrister, he considers the alternative case and adds ‘that standing outside the Supreme Court on the prorogation case was also an amazing thrill and arguably more important work. Comedy is entertainment but those cases I covered really mattered and they were critically important to people’s lives. However, I get a particular satisfaction from seeing something being developed from an idea, through writing, production, broadcast. That’s why we all do it. That’s why all writers do it.’

Reporting for the BBC outside the Old Bailey and Royal Courts of Justice. In 2018 Clive was made an Honorary Bencher of the Middle Temple in recognition of his legal journalism.

The Duke, co-written by Clive Coleman, is on general release in February 2022.

‘I have always done what I found really interesting and stimulating. I realise I have been incredibly lucky to have been able to do that. I have been a barrister, sitcom writer, written film scripts and plays. I have also been a BBC broadcaster and journalist and presented a Panorama,’ says Clive Coleman.

The UK is very much open but we are having this conversation over Zoom in September. Perhaps unbecoming of a barrister, I quickly inform Clive that my preparation for this interview began on Wikipedia. There I was blown away by what he later describes as the ‘ridiculous variety’ of his career. He gives the kind of warning that would be expected from a former journalist and teacher: ‘You can’t believe everything you read on [Wikipedia]’ but he assures me that relying on his page would not put me in contempt with Counsel’s readers.

Clive studied English literature at the University of York before taking a law conversion course. Called to the Bar in 1986, he first practised from the Chambers of Robin Stewart QC where, he says, ‘like almost every young barrister in a general common law set, you did anything that came through the door’. This meant Crown Prosecution Service lists, a few jury trials, criminal work that spun off from the civil side and knockabout work in the Magistrates’ Court. He lights up when talking about those early experiences as a courtroom advocate – it is clear this is what he loved about being a barrister.

When reflecting on his first choice of career, I learn that this love was developed at a much earlier stage. He tells me about his father who ‘was a sort of a lawyer; a patent attorney who had come from a very humble background in Leeds. He had always wanted to be a barrister, but never had the money.’ Eventually, his father got a state scholarship and did an engineering degree at Oxford University. Clive describes his father’s office on Fleet Street and recalls walks with him around the Inns of Court. He jokes: ‘Our family are just words… it is all we can do. We could not add up a row of figures to save our lives, but we are very wordy. I grew up in an atmosphere where language and how you expressed yourself and structuring an argument was always quite important.’ As somebody who also enjoys being on stage, I am glad he admits: ‘There was also certainly an aspect of performing that I liked about it.’

However, in 1990 Clive left full-time practice at the Bar to teach on what was then the Bar Vocational Course (BVC). Alongside this he was able to develop a creative writing career, which comprises the largest part of his Wikipedia page. Sticking close to his ‘practice area’, the first big show Clive wrote was Chambers, a comedy series set around barristers.

When I ask about the impetus for writing the show, he explains: ‘There is something grand and theatrical about a courtroom and being a barrister. There is almost a feeling that barristers are not as desperate and ambitious as everyone else [though] of course they are. With the tremendous tradition, grandeur and costume on the one hand, and the fact that barristers were just like everyone else and as capable of taking shortcuts, and those kinds of things, I thought there was a good comic interface.’ Clearly, others agreed. The show launched on BBC Radio 4 in 1996, ran for three series, before transferring to BBC One for two hit television series.

I push Clive on whether his creativity is restricted to writing about the law. He says that every writer should write what he knows. However, there is more to it and he returns to the point about language: ‘Courtrooms are fantastic settings for the very intricate use, and sometimes hilarious misuse, of language. I just find that type of writing is something that I really, really enjoy,’ he says.

Reflecting on memories from early practice, he describes ‘moments where barristers don’t know what on earth they are going to say next, [but] they still sound very, very fluent. So, they will say things like, “And... I have two points to make and those are these, if I may, and I will take the first of those two points now…” They haven’t actually said anything, but it sounds fantastic. I love all the barristers’ tricks of the trade.’ I pause to take some notes for my next hearing in front of a district judge.

Since Chambers, Clive has amassed a range of writing credits on popular comedy shows. However, I cannot waste the opportunity to ask him about his experience writing for one of my favourite legal dramas: The Bill. I have fond memories of sitting next to my dad watching it as a child. However, Clive explains that writing on it ‘was really hard because you were part of a massive jigsaw puzzle, and the pieces were changing fairly regularly. I admired the show, but it was also pure drama and I think I was missing doing gags. Comedy drama is about as much drama as I can handle!’ I wonder whether we both shed a tear when Sun Hill closed its doors.

Nonetheless, as an avid comedy lover and very amateur comedy writer, I understand what keeps pulling him back. He tells me about one of his early opportunities with the BBC, writing comedy news radio sketches. ‘The story was about Sarah Ferguson having her toe sucked by her Texan financial adviser, a guy called John Bryan. Someone in the room said, “Any sketch ideas on this?” “Not tonight, darling, I’ve got a verruca,” was the first gag and then people just [started] topping each other out.’

As he tells the story, he describes that feeling of elation of being in a room with minds working in a similar way. ‘I cannot paint a picture. I’m not musical. But a painter or musician would feel at home with other artists in this way. I really enjoy it. I think this is using my mind in the way that it was meant to be used. So I will do a bit more of it.’

We switch to his current creative project – The Duke – a comedy film he co-wrote with long-term writing partner Richard Bean. It tells the story of Kempton Bunton, a Newcastle cab driver prosecuted for the 1961 theft of Francisco Goya’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington from the National Gallery in London. He describes it as ‘a fantastic true story from the 1960s that everyone had forgotten about and culminated in a fantastic trial at the Old Bailey’. For something like this to be brought to life, ‘you need genius performers for it to absolutely catch fire and obviously a great director’. I can hear the excitement as he reels off the star-studded cast – Jim Broadbent, Helen Mirren, Matthew Goode, Sian Clifford, Fionn Whitehead and Anna Maxwell Martin – directed by the ‘brilliant’ Roger Michell. The film premiered at Venice in June 2020 to positive acclaim. The pandemic means the rest of us will have to wait until February 2022 for its release. (Very sadly, after my interview with Clive, I learn that Roger Michell, the director of The Duke, died suddenly. Roger will not now see the film released and Clive tells me how devastated all those involved in the film were.)

As we continue our discussion, I am interested in exploring Clive’s journalism career. From 2004-2010, he presented the BBC’s flagship legal analysis programme: Law in Action on Radio 4, a role for which he had no formal training. I ask him what is more nerve-wracking: standing up in the Court of Appeal in front of three brilliant judges, having your arguments dismantled limb by limb, phrase by phrase, or to be a live broadcaster. Without hesitation he says, ‘a live broadcaster… because if you get it wrong in court, maybe 20 people would get to know about it. But if you do it in front of four million people, it is utterly terrifying, humiliating and the stakes are just so much higher. No contest.’

He is quick to say, however, that ‘my lawyer’s training helped me avoid some of the very obvious elephant traps.’ This is a point he makes a number of times – ‘the discipline, analysing things critically, being able to go to the absolute essence of a piece of information to winnow out the stuff you don’t need, to focus and make the most of the really important stuff. All that is fantastically good training. That’s the thread that has really gone through pretty much everything I’ve done.’

In 2010, he took on a new role in journalism when he became the BBC’s Legal Correspondent, a position the broadcaster had previously left unfilled. During this time, he covered some of the biggest domestic and international legal stories including the London Riots, the courts backlog and release of the London Bridge terrorist, Usman Khan. He explains: ‘My brief was The Law, not just landlord and tenant or defamation. It was divorce, privacy, property, international law, human rights law, judicial review... it was everything!’

I laugh when he describes how, as a legal reporter, his experience as a BVC teacher meant he would be sitting in court and realise, ‘I had taught the QC and then I thought, hang on, I’m sure I taught the judge. There are now some High Court judges that I actually taught.’ There is something poetic about his diversity of careers meeting in the courtroom.

The story that has had the greatest impact on him, no doubt, is the prorogation case. He explains: ‘It was a massive case. It was a fantastic insight for people into how the constitution of the country actually works. This clash, if you like, between the very powerful executive on the one hand, and the independent judiciary on the other who, through the mechanism of judicial review, have the power to stop Ministers in their tracks if what they are proposing to do or have done is unlawful.’

He goes on: ‘I think people didn’t quite get that that could happen and that nobody is above the law.’ It was this story for which he won the Bar Council Legal Broadcasting Award in 2019 for the second time. We take a brief moment to fawn over Lord Pannick QC.

We are nearing the end of the interview and we discuss his most recent work, which is absent from his Wikipedia page: litigation PR. He explains that ‘there is a case that can be won and lost in the courtroom and there is a case that can be won and lost outside the courtroom as well,’ citing the example of Harry and Meghan and their litigation with the Daily Mail. Adding another string to his legal bow, Clive now works with Maltin PR assisting law firms in this area.

On my count, Clive has had at least five careers. I would be doing a disservice if I did not end our interview by asking him which was his favourite.

‘If I’m honest, I think the thing that I ultimately, probably, feel I get most satisfaction from is constructing a piece of fiction; whether it’s a half-hour sitcom or a one-and-a-half-hour film script that works.’ Like any good barrister, he considers the alternative case and adds ‘that standing outside the Supreme Court on the prorogation case was also an amazing thrill and arguably more important work. Comedy is entertainment but those cases I covered really mattered and they were critically important to people’s lives. However, I get a particular satisfaction from seeing something being developed from an idea, through writing, production, broadcast. That’s why we all do it. That’s why all writers do it.’

Reporting for the BBC outside the Old Bailey and Royal Courts of Justice. In 2018 Clive was made an Honorary Bencher of the Middle Temple in recognition of his legal journalism.

The Duke, co-written by Clive Coleman, is on general release in February 2022.

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

In the first of a new series, Louise Crush of Westgate Wealth considers the fundamental need for financial protection

Unlocking your aged debt to fund your tax in one easy step. By Philip N Bristow

Possibly, but many barristers are glad he did…

Mental health charity Mind BWW has received a £500 donation from drug, alcohol and DNA testing laboratory, AlphaBiolabs as part of its Giving Back campaign

The Institute of Neurotechnology & Law is thrilled to announce its inaugural essay competition

How to navigate open source evidence in an era of deepfakes. By Professor Yvonne McDermott Rees and Professor Alexa Koenig

Brie Stevens-Hoare KC and Lyndsey de Mestre KC take a look at the difficulties women encounter during the menopause, and offer some practical tips for individuals and chambers to make things easier

Sir Geoffrey Vos, Master of the Rolls and Head of Civil Justice since January 2021, is well known for his passion for access to justice and all things digital. Perhaps less widely known is the driven personality and wanderlust that lies behind this, as Anthony Inglese CB discovers

The Chair of the Bar sets out how the new government can restore the justice system

No-one should have to live in sub-standard accommodation, says Antony Hodari Solicitors. We are tackling the problem of bad housing with a two-pronged approach and act on behalf of tenants in both the civil and criminal courts